Solana has one of the highest staking rates among all blockchains. As of now, 65% of the circulating SOL is staked, which is significantly higher compared to ETH’s 29%. Several factors contribute to this difference, including the attractive yields ranging from 8% to 12% that Solana provides, as well as a positive outlook for SOL’s performance among its holders. However, another important factor is the Solana Foundation Delegation Program (SFDP), which accounts for a significant portion of the staked SOL.

Helius wrote a comprehensive and detailed piece about the Program, but almost a year has passed since its publication, making it a good time to revisit the subject. In this article, we will examine the current state of the program to understand its effect on Solana’s validator landscape and what the network might look like if the SFDP were to end.

The Solana staking market can be categorized into three distinct segments:

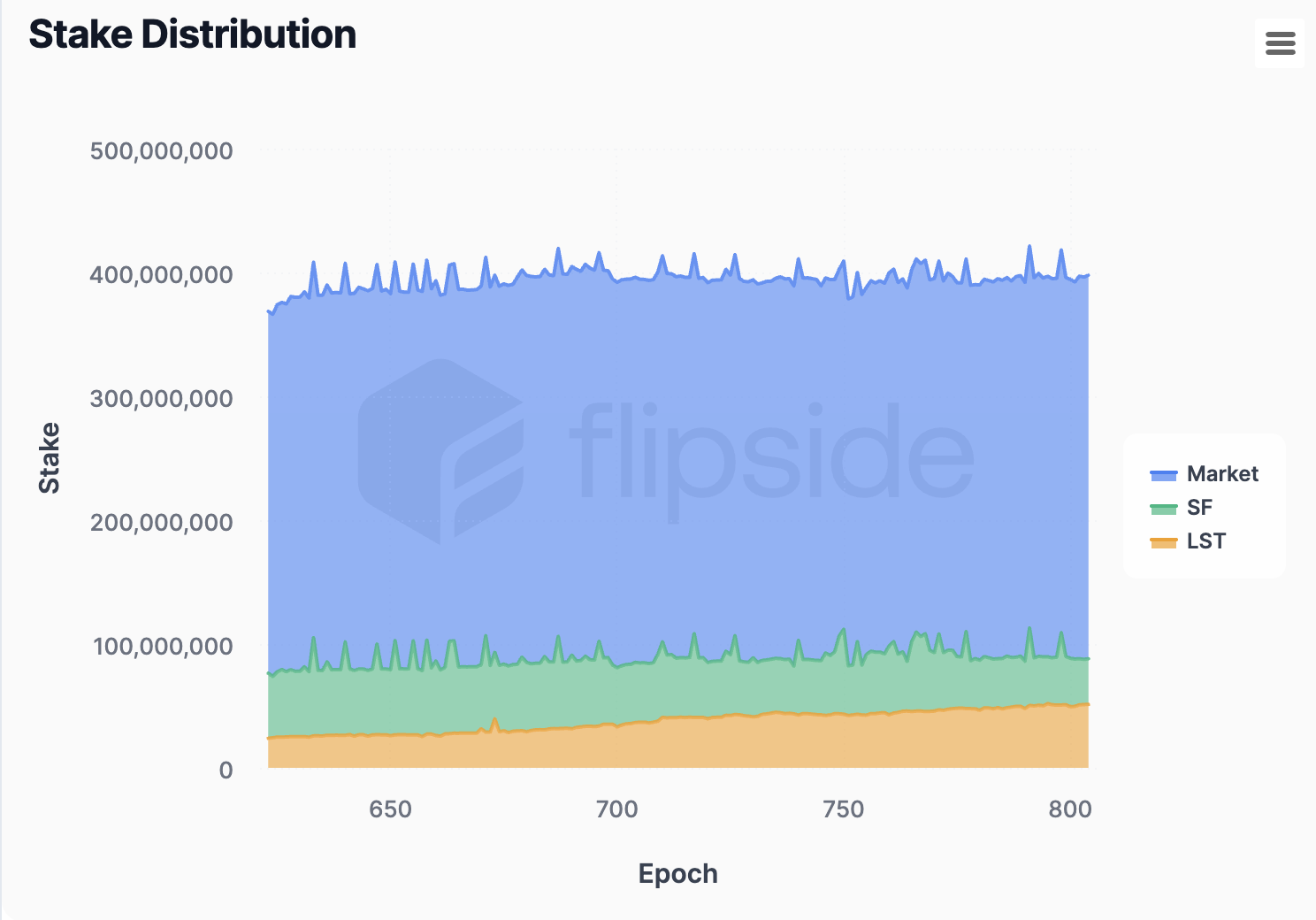

As of epoch 804, the total amount of staked SOL is 397 million, with the general market delegating 309 million, the Solana Foundation 37 million, and LSTs contributing 51 million. Over time, we have seen steady growth in LST stake and a decrease in SF delegations, which now make up slightly less than 10% of the total stake.

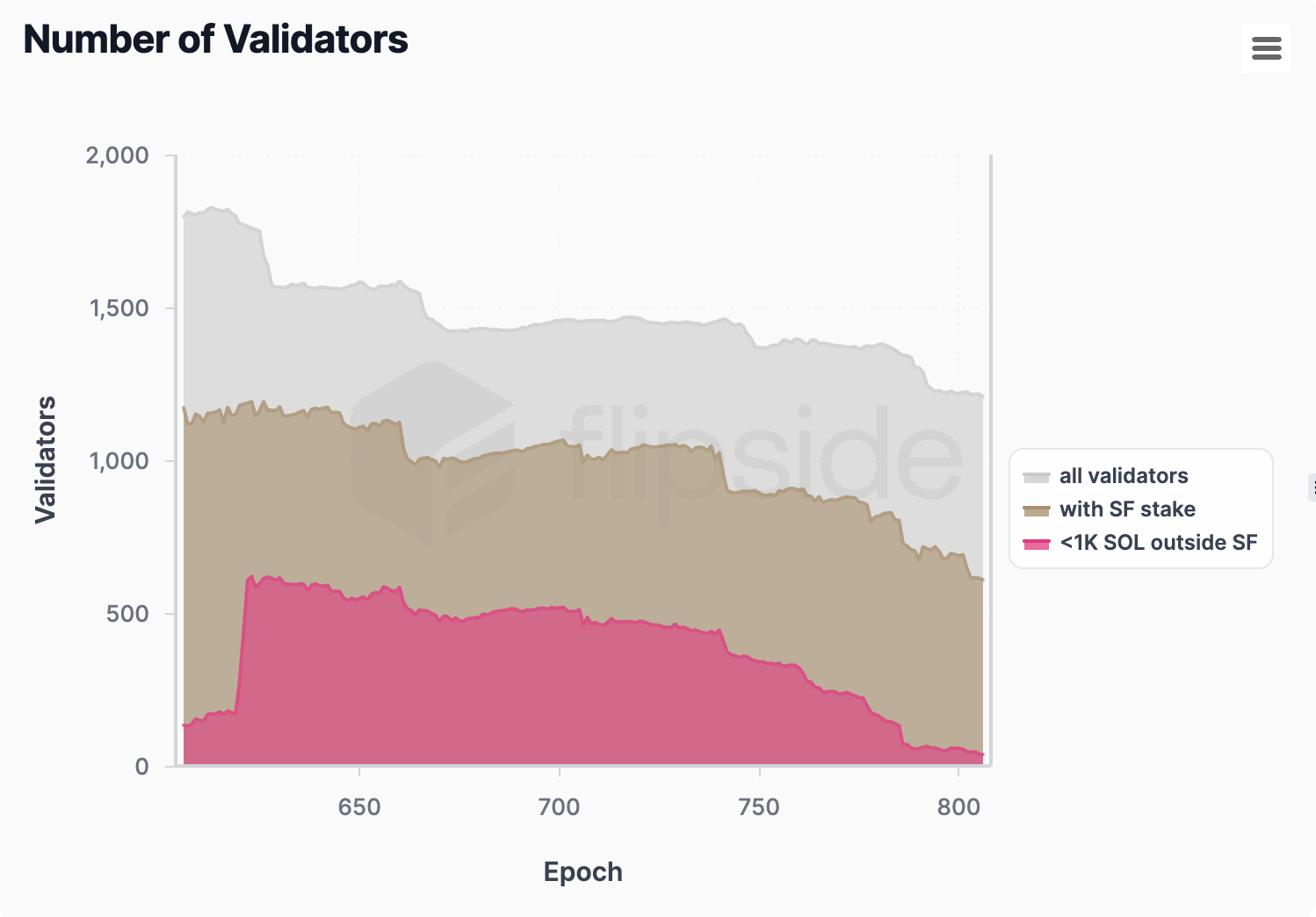

Solana stake is managed by a total of 1,216 ****validators, down from a peak of 1,800. The number of validators receiving delegations from SFDP has decreased from over 1,100 to 616, which still makes up 50% of the entire validator set, representing a significant decrease from the initial 72%. We also observe the validators with less than 1K SOL delegated outside of SF—currently at 46, down from over 600.

The 1K SOL threshold is important because SF decided to stop supporting validators that receive a Foundation delegation for more than 18 months and are not able to attract more than 1K SOL in external stake.

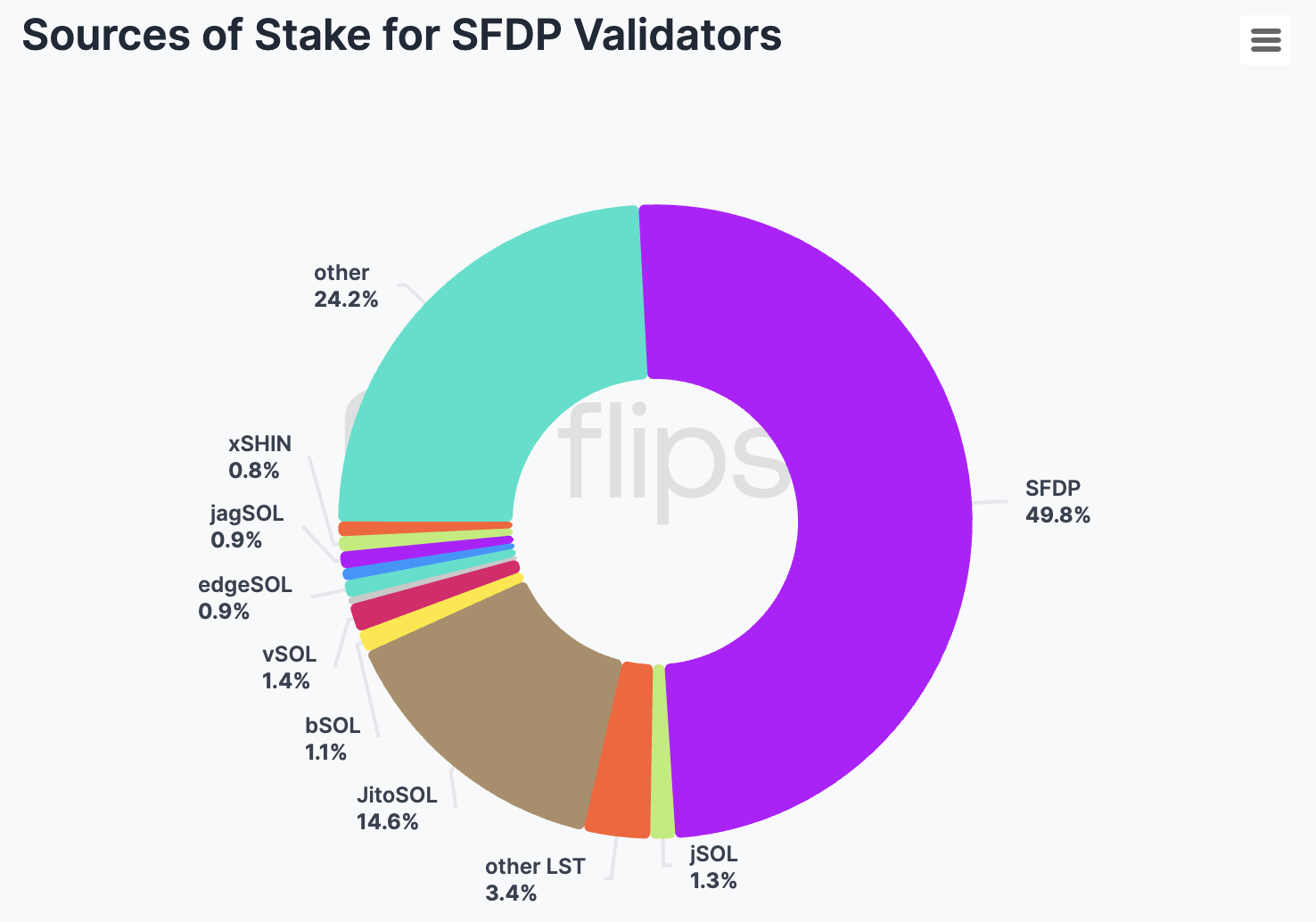

Delegations from the Program make up 49.8% of the total stake delegated to validators participating in SFDP. This is significant, but it also shows that over half of the stake comes from other sources, which is a positive sign.

Another opportunity (or lifeline) for smaller validators is provided by LST staking pools, which collectively make up 26% of the stake delegated to validators participating in the SFDP. Notably, the Jito stake pool, represented by the JitoSOL token, has accumulated 17.8 million SOL out of a total of 397 million SOL currently staked. Due to this substantial amount, being one of the 200 validators receiving delegation from the pool is highly rewarding, currently by around 89K SOL. Of the 17 million native SOL in the Jito pool, nearly 11 million, or 65%, ****are delegated to SFDP participants.

For Blaze (bSOL), another popular staking pool, 0.8 million of the 1.1 million SOL, accounting for 72%, is delegated to SFDP participants. For JPOOL (jSOL), it’s 83%, and for edgeSOL, it’s as high as 87%. Many of the LST pools highly depend on outstanding voting performance, resulting in a cut-throat competition between validators to receive delegation. The validators often run backfilling mods to increase the vote effectiveness and receive stake. Chorus One has analyzed these client modifications in a separate article.

We also observe that the SFDP and LSTs are vital for maintaining Solana's decentralization. This results from the geographical restrictions imposed by the Foundation and staking pools on validators.

When examining the total stake of validators participating in SFDP, only 31 had accumulated more than 300K SOL, while 249 had less than 50K SOL delegated.

Looking at the top 20 validators individually, the validator with the highest stake, Sanctum, accumulated a total of 850K SOL in delegations. In contrast, the 20th validator's total stake drops to 351K SOL. The size of the SFDP delegation doesn’t exceed 120K SOL in this group.

In the remaining group of 589 validators, the median total stake is 65K SOL, and the median SF delegation is 40K SOL, indicating that many validators rely heavily on the Foundation for their operations.

The node operating business has become very competitive in recent years. This is especially true on Solana, where validators often run modified clients or lower their commissions to unhealthy levels to gain an advantage. And like any other business, you can't stay unprofitable for too long.

And what does too long mean on Solana? To answer this question, we group validators into cohorts. We group time into periods of 10 epochs: every 10 epochs, a new period starts. Every period, a new cohort of validators emerges. We can follow these cohorts and see how the composition of the validator set changes over time, and in which period the validators started. For this analysis, we only consider validators with at least 20k SOL at stake.

Based on the first graph, the survival rate for most cohorts falls below 50% after approximately 200 to 250 epochs. Similarly, the second graph shows that validators who started around epoch 550 see the steepest drop in survival rates. This suggests that the too long in terms of unprofitability on Solana means around 250 epochs.

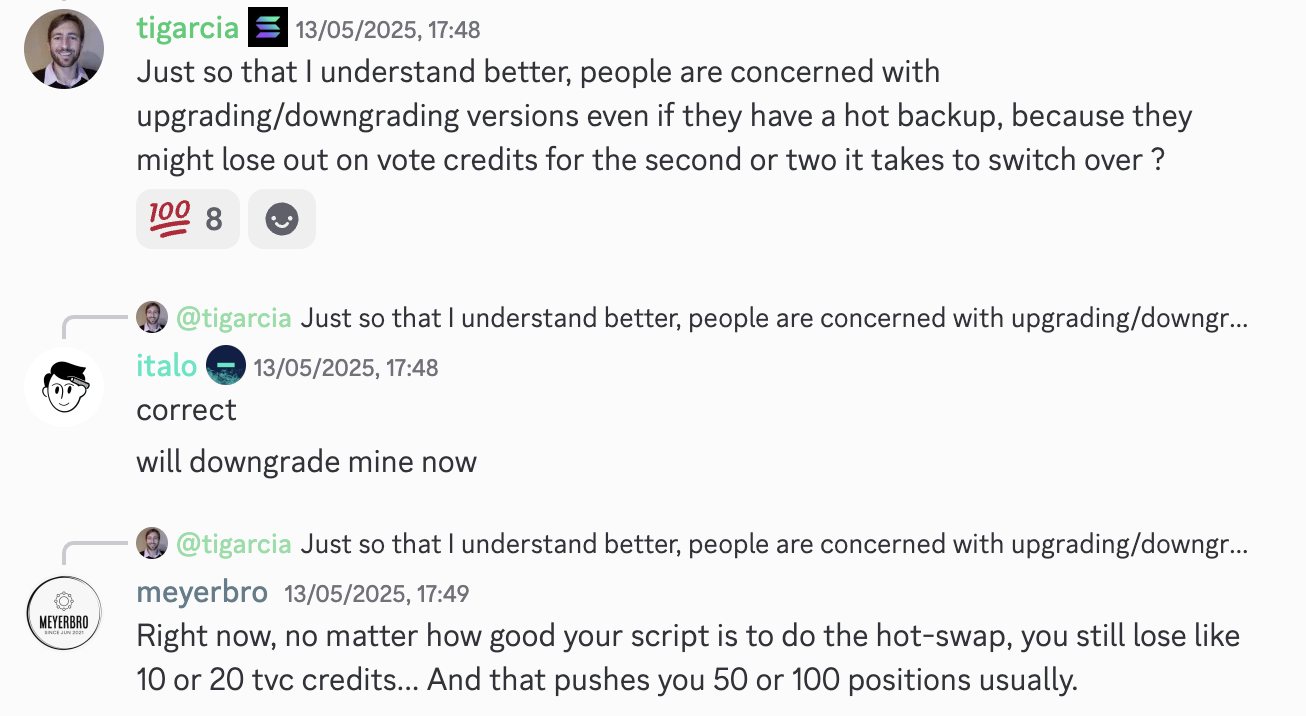

One indicator of how fiercely competitive the smaller validator market has become is the scramble to join the JitoSOL set, where validators hesitate to upgrade the Agave client because they risk losing several vote credits during the update. Any loss of vote credits is problematic since Jito updates the validator pool only once every fifteen epochs. Additionally, being outside the set decreases a validator’s matching stake from SFDP. Therefore, with the current 89K SOL Jito delegation goal, a validator could lose 178K stake if something goes wrong during the update.

Validators earn revenue via:

Of the three on-chain traceable revenue sources, MEV and block rewards are highly dependent on network activity. In contrast, inflation rewards are a function of the Solana inflation schedule and the ratio of staked SOL.

Validator performance also impacts yields. Opportunities to increase inflation rewards are limited, as almost all validators receive close to the maximum vote credits possible. Some validators overperform in voting, but APY gains from it are close to a rounding error—0.01%. Currently, the inflation rewards produce the highest gross (before commission) returns of around 7.3% annually, when compounded. The most effective voting optimizations include mods that enable vote backfiling. This opportunity, however, could be short-lived as intermediate vote credits update rolls out in the coming months. That is, unless the update is entirely abandoned because of the introduction of Alpenglow.

MEV tips and block rewards see higher upside from optimizations. Based on current activity (June 2025), tips yield between 0.75% and 0.9% in annualized gross APY, while block rewards yield between 0.55% and 0.65%. Both have a luck factor in it—if there’s a particularly juicy opportunity, e.g., for arbitrage, the searchers will be willing to pay more to extract it. Thus, the bigger the stake the validator has, the higher the chance it will receive outsized tips or block rewards. The validator optimizations for MEV tips and block rewards involve updates to the transactions ingress process or the scheduler.

In absolute terms, all revenue sources depend on the stake a validator has.

Solana is infamous for its high-spec hardware requirements and the overall costs it imposes on validators running the nodes. These costs include:

The total cost of running the Solana node, excluding any people costs, in June 2025 ranges from $90,000 to $105,000.

To establish the profitability of a validator participating in an SFDP, we will:

On the revenue side:

On the costs side:

With the above assumptions, we measure the profitability of validators participating in SFDP considering their: (1) total active stake; (2) only outside stake, without SF delegation; (3) only outside stake, but assuming no voting costs.

If the current market conditions and network activity remain unchanged for the entire year, in the first group**,** 295 SFDP validators would be profitable (48%), with a median profit of $134,283. Conversely, 319 validators are facing a median loss of -$51,473.

It is important to note that the graphs in this section are capped at $700,000 on the y-axis for clarity; however, some validators have profits that exceed this amount.

However, the stake received from the Foundation is not evenly distributed among all validators. The average stake delegated from the Program to profitable validators is 94,366 SOL, while to unprofitable ones, it is only 26,969 SOL.

The last profitable validator holds a stake of 33,242 SOL from SFDP and 21,141 SOL from outside sources, which enables it to earn $1,710.

There is a noticeable difference in commissions between the profitable and unprofitable groups: the profitable validators have an average inflation commission of 1.92%, compared to 1.51% in the unprofitable group. Similarly, the average MEV commission in the profitable group is 7.36%, compared to 5.44% in the unprofitable group.

Things get less rosy if we consider only the outside stake, without the SFDP delegation. The number of profitable validators decreases to 200, which accounts for 32% of the total, with a median profit of $35,692. The number of unprofitable validators increases to 414, with a median loss of $78,912.

The last profitable validator has 95,030 SOL in outside stake (although, with 0% inflation and MEV commissions) and earns $126.31. The minimum outside stake guaranteeing profitability is 56,618 SOL, with commissions at 5% inflation and 10% MEV. This is enough to get $5,441.52.

Among the profitable validators, the average inflation commission is 1.75%, while the average MEV commission is 7.57%. For the unprofitable nodes, the commissions decrease to 1.7% and 5.8%, respectively.

It is well known that voting costs impact validators the most. With the SOL price at $161 (as used in this analysis), validators spend around $59,063 on voting only. For this reason, node operators have long advocated for the reduction or complete removal of voting fees. This wish will be finally fulfilled with Alpenglow, Solana’s new consensus mechanism announced by Anza at Solana Accelerate in May 2025. It is ambitiously estimated that the new consensus will replace TowerBFT in early next year.

We analyze the scenario in which voting doesn’t generate costs. Even if we only consider the outside stake, it makes a big difference.

The number of profitable validators increases by 50%, from 200 to 303, compared to the second scenario. The median profit in this group reaches $74,328. While there are still 311 unprofitable validators, the median loss falls to $23,576.

The minimum stake required to guarantee profitability is 17,988 SOL, representing a 68% decrease compared to the scenario that includes voting costs.

Still, the difference in average commissions is impactful—1.92% on inflation and 7.29% on MEV in the profitable group compared to 1.51% and 5.47% in the unprofitable one.

The SFDP continues to play a vital role in the Solana ecosystem. Recently, the Foundation has shifted its focus to support validators who make meaningful contributions to the Solana community and actively pursue stake from external sources, aiming to create a more engaged and sustainable validator network.

With a more selective approach from the Foundation, LSTs come as a crucial source of stake for smaller validators. SOL holders like them, which is evident in their constantly increasing stake; however, the competition to get into the set is prohibitively tough. Still, the importance of SFDP’s stake matching mechanism cannot be understated in light of delegations from LSTs.

Together with LSTs, the SFDP stake makes up 22% (88 million SOL) of the total SOL staked. Since both impose geographical restrictions on validators, they are crucial to keep Solana decentralized in an era where even negligible latency improvements from co-location are exploited.

Currently, many validators remain unprofitable, even with support from SFDP. Commission sizes play a role here—setting them too low doesn’t seem to help with getting enough stake to run the validator profitably.

Another force negatively impacting the validators’ bottom line is voting cost. When network activity and SOL price are high, this is the time when validators should offset the periods with little action. Unfortunately, due to the voting process, a significant portion of revenue is lost. The solution, Alpenglow, is on the horizon, and it cannot come fast enough to reduce pressure on validators. Eliminating the voting costs should enable the Solana Foundation to step away further and let the network develop on the market’s terms, without excessive subsidy.