In The Road to Internet Capital Markets, core Solana contributors outline a vision in which the network becomes the venue for global asset trading, defined by best prices and deepest liquidity. The main claim is that decentralized markets can absorb information from anywhere in the world in near real time. With Solana’s planned multi-leader architecture, or multiple block producers operating in parallel, the network can, in principle, reflect region-specific news faster than geographically concentrated TradFi venues.

While Solana can offer a global latency advantage, speed alone is not sufficient for market dominance. What ultimately determines competitiveness is execution quality, the true cost of a trade relative to the asset’s fair price. Execution quality can be measured via:

Understanding these is essential because execution quality is fundamentally about market making. How liquidity is provided, how makers manage inventory, and how they protect themselves from informed flow. In TradFi, these mechanics are handled by wholesalers like Citadel and Virtu. On Solana, they are increasingly managed by proprietary AMMs (prop AMMs) that operate as onchain market makers.

This article gives a practical introduction to market making on Solana:

Markets function only when participants can trade size with limited price impact. Liquidity depends on confidence. Market makers supply it by continuously quoting both sides, but they will only do so if they expect to survive contact with informed flow. When they’re repeatedly “picked off”, selling before prices rise or buying before they fall, they widen spreads or withdraw entirely.

Execution quality, therefore, is about building an environment where liquidity providers can quote tightly without being punished for doing so. This is why the ICM roadmap emphasizes mechanisms that protect market makers even if that slows price discovery.

A venue can be global, fast, and permissionless, but if execution is consistently worse than in TradFi, the ICM vision collapses. Conversely, if Solana can match or exceed TradFi’s execution quality, the case for permissionless global markets becomes irrefutable.

Execution quality is the determinant of market competitiveness. For retail, wider spreads led to worse fills, which in turn gave rise to Payment for Order Flow (PFOF) models such as Robinhood’s (Levy 2022). For institutions, a few basis points equate to millions in annual execution costs. In DeFi, wider spreads translate into higher swap costs and declining crypto user retention. Traders focus on venues where all-in execution costs are lowest and most predictable.

To understand how Solana can compete, we adopt a formal, data-driven framework. The global standard for measuring execution quality remains the one enforced by the U.S. SEC, codified in SEC Rule 605.

Modern U.S. equity markets are fragmented across exchanges, wholesalers, and alternative trading systems. The regulatory anchor is the National Best Bid and Offer (NBBO), which aggregates the tightest bids and asks from all lit exchanges at a given moment.

Retail investors rarely interact with those exchanges directly. Instead, their brokers (Robinhood, Schwab, Fidelity) route orders to wholesale market makers such as Citadel, Virtu, and Jane Street. These firms internalize the flow, providing price improvement relative to NBBO and, in return, paying the broker under PFOF arrangements. Market makers want to trade against retail because it is less informed, and they are willing to subsidize brokers to access that flow.

Institutional investors, by contrast, interact more often on exchanges or dark pools, where execution quality is worse, liquidity is thinner, adverse selection risk is higher, and spreads are wider, a structural disadvantage compared to wholesaler-handled retail flow (Zhu, 2014). This segmentation creates two very different execution experiences:

The SEC mandates monthly disclosures under Rule 605 to bring transparency into execution quality. These reports require wholesalers and exchanges to publish detailed statistics on how retail orders were executed.

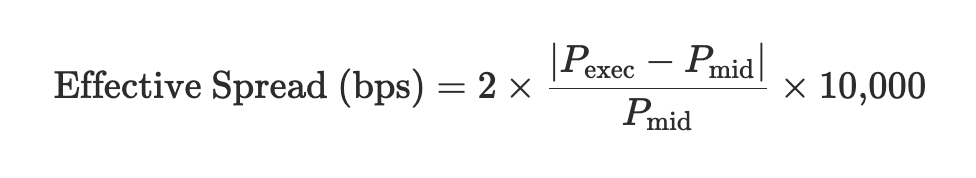

These statistics include effective spread, which is a canonical metric, defined as twice the absolute difference between the execution price and the NBBO mid, expressed in basis points:

Equation 1: Effective spread definition, source: 17 CFR 242.600(b)

This measure is a round-trip comparable. The ×2 convention assumes that a one-way trade should be evaluated as half of a full buy-sell round trip.`

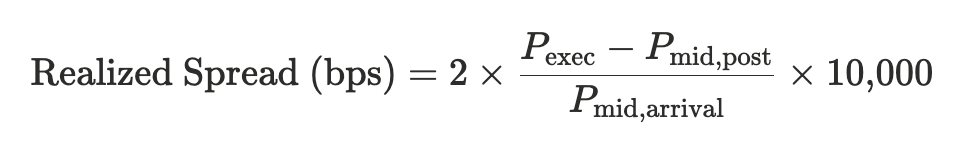

Rule 605 also reports realized spread, which compares the execution price to the midpoint shortly after execution. It measures adverse selection, or whether the price moved against the liquidity provider after filling the order:

Equation 2: Realized spread definition, source: 17 CFR 242.600(b)

Positive realized spreads imply the order flow was uninformed. Negative values mean the market maker was picked off, indicating toxic flow.

In this article, we will focus on presenting effective spreads.

To ground execution quality in data, we analyzed SEC Rule 605 reports across wholesalers and aggregated marketable orders to estimate effective spreads in basis points relative to traded notional size.

.png)

Figure 1: TradFi effective spreads (bps) vs. USD notional size

Execution quality in US equities scales sharply with both liquidity and trade size.

Spreads widen with trade size relative to available liquidity. In traditional markets, a price curve emerges organically from the balance between a market maker’s inventory constraints and the risk of trading against informed flow. Each incremental unit of size consumes balance sheet and increases adverse selection exposure, steepening the effective cost.

This behavior is not unique to TradFi. Onchain markets obey the same logic. Legacy AMMs aim to approximate this relationship mechanically by using deterministic pool curves rather than adaptive inventories. Prop AMMs on Solana, by contrast, collapse that abstraction entirely. They are market makers in the traditional sense, quoting prices based on inventory, risk, and order-flow information.

Classic AMMs, such as constant-product and concentrated liquidity, no longer dominate Solana’s volume, but they still underpin much of the onchain market structure. Their design remains the reference point for decentralized execution quality.

Constant-product AMMs distribute liquidity uniformly along the price curve, ensuring continuity but leaving most capital idle and spreads structurally wide. Concentrated liquidity AMMs address this inefficiency by allocating liquidity more tightly around the active price, improving capital efficiency and near-mid execution.

Proprietary automated market makers are a Solana-native innovation. They follow the same deterministic settlement rules as classic AMMs, but replace their curve-based pricing logic with model-based quoting.

.png)

Figure 2: Share of Solana DEX volume by pool type. Prop AMMs now account for roughly 65% of on-chain trading volume, surpassing traditional CLAMMs.

Instead of encoding liquidity as a fixed function of reserves, a prop AMM computes executable quotes from a live strategy that reflects inventory, volatility, and hedging across markets.

Structurally, a prop AMM behaves like an onchain quoting engine connected to an offchain risk model.

This design eliminates the inefficiency of passive CLAMMs, in which LPs continuously provide liquidity on both sides of a curve and incur impermanent loss.

Prop AMMs quote **when their internal model deems the trade safe or profitable. Pricing is rewritten after each fill, redrawing the curve around the new inventory position. As a result, execution quality depends on model precision, update latency, and inventory limits.

The rise of prop AMMs on Solana marks a transition from curve-based liquidity to TradFi-like quote-based execution, only without custodial intermediaries.

Some of the most prominent AMMs on Solana include HumidiFi, operated by Temporal; SolFi, developed by Ellipsis Labs; Tessera V, run by Wintermute; and other, smaller players.

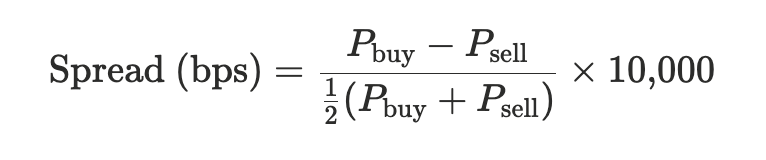

To evaluate Solana’s ICM vision, we adapt Rule 605's logic to on-chain data. DeFi lacks a true NBBO because AMMs do not publish standing bids and asks. Instead of quote-based spreads, we infer execution quality directly from realized trades.

We group all executions within the same Solana slot and compute volume-weighted average buy and sell prices for each venue. Their difference represents the realized bid–ask width implied by actual trading activity at that moment:

Equation 3: Effective spreads onchain

Aggregating these slot-level values into volume-weighted averages gives a venue-level execution metric directly comparable to TradFi spreads. While this diverges from the NBBO-based definition, which uses public quotes rather than trades, the underlying economic interpretation is the same: the round-trip cost of immediate liquidity.

This framework allows us to measure how efficiently Solana’s DeFi venues deliver execution, expressed in the same units used for equity markets. We apply it to both classic AMMs and proprietary AMMs.

SOL is the deepest and most competitive market on Solana, making it the clearest choice for comparing AMM designs. The market has become increasingly crowded, with multiple venues active across the entire size ladder. Humidifi leads with almost 65% of SOL–USDC volume recently.

.png)

Figure 3A. SOL–Stablecoin DEX volume by venue (Blockworks Research, 2025).

Execution on SOL–USDC is uniformly strong across all AMM types, but venue-specific patterns emerge when trades are grouped by notional size.

Across all trade sizes, from 100 USD up to 1M USD, prop AMMs (HumidiFi, Tessera, ZeroFi, SolFi, GoonFi) sit at the front of the spread distribution. Their defining feature is size invariance, meaning spreads barely change as trade size increases.

HumidiFi quotes 0.4–1.6 bps across nearly the entire size ladder, only increasing to 5 bps at $1M. Tessera and ZeroFi cluster in the 1.3–3 bps range, maintaining these results even at 100k.

Pop AMMs set the lowest spreads on Solana and remain stable at scale.

.png)

Figure 4A. Effective spreads (bps) by trade-size bucket across SOL AMMs. Bubble area proportional to traded volume.

Curve-based AMMs (Raydium, Whirlpool/Orca, Meteora, PancakeSwap) behave differently:

Orca remains the dominant venue by volume across all buckets above $50k.

In 2025, BTC liquidity on Solana cycles through several venues. Orca leads for most of the year, typically handling the largest share of weekly volume. Meteora remains the main secondary venue, with a steady but smaller footprint. Prop AMMs begin to matter as the year progresses: SolFi and ZeroFi start taking meaningful share from mid-2025 onward, and Humidifi emerges later with growing market share.

.png)

Figure 3B: Bitcoin DEX volume by venue (Blockworks Research, 2025).

BTC execution mirrors the SOL patterns but with more noise due to thinner depth. Prop AMMs dominate the low end of spreads, while classic AMMs widen more quickly with size.

.png)

Figure 4B: Effective spreads (bps) by trade-size bucket across BTC AMMs. Bubble area proportional to traded volume.

Classic AMMs remain less competitive compared to propAMMs on BTC:

Overall, prop AMMs set the tightest BTC spreads, while classic AMMs account for most of the trading volume, but at higher and more size-sensitive costs.

TRUMP is a useful benchmark for meme execution. Its liquidity is large enough (including a ~$300M DLMM pool) to behave like a mid-cap, yet volatile enough to stress AMM pricing models. Spreads are an order of magnitude wider than in SOL or BTC, but the relative performance across AMM types remains informative.

Prop AMMs again show flexible but not dominant pricing:

Prop AMMs do not dominate TRUMP execution the way they do in SOL.

.png)

Figure 4C: Effective spreads (bps) by trade-size bucket across TRUMP AMMs. Bubble area proportional to traded volume.

Classic AMMs cover most TRUMP execution with Meteora quoting 20–25 bps across almost all sizes, a profile tied directly to its fee floor as trades stay within a single, huge liquidity bin of the aforementioned pool.

Execution quality on Solana is no longer constrained by AMM mechanics, but by balance-sheet scale and risk tolerance.

Classic AMMs behave as their design predicts. Fees and liquidity placement impose a spread floor, while limited depth causes execution costs to rise nonlinearly with trade size. Outside of SOL, these venues still carry most of the flow, but only by accepting higher and more size-sensitive execution costs.

Prop AMMs, by contrast, show the characteristics of true market makers. Their spreads are tighter and largely invariant to size across a wide range, showing that pricing is driven by inventory and risk limits rather than fixed curves.

This difference points to the remaining execution gap. Where Solana underperforms TradFi, the cause is primarily capital scale. TradFi wholesalers compress spreads at multi-million-dollar sizes by deploying massive balance sheets and internalizing flow across venues. On Solana, comparable execution quality already exists, but only up to the inventory limits of today’s prop AMMs.

With that framing, the implications for Solana’s Internet Capital Markets vision become clear.

Prop AMMs define the execution frontier. They deliver sub-1–5 bps spreads on SOL with minimal size dependence; on BTC, Humidifi anchors execution at 2–4 bps; and even on volatile tokens like TRUMP, prop AMMs are the only venues able to break below the 20–25 bps floor imposed by fees in substantial Meteora’s liquidity pools. Their performance comes from market-maker–style quoting: inventory-aware, model-driven, and updated on top of every block.

Classic AMMs show a more size-sensitive regime. SOL pairs cluster around 5–9 bps for typical flow; BTC spreads widen sharply at higher notionals; and TRUMP prices settle near the fee floor. They provide the liquidity backbone, but not the best execution.

Compared to TradFi, Solana is increasingly competitive for small and mid-sized orders.

Rule 605 data places S&P-500 names in the sub-1–8 bps range, mid-caps in the 3–25 bps range. Prop AMMs already match or exceed this for sub-$100k trades, especially in the native SOL markets. The remaining performance gap stems from scale: TradFi exchanges achieve execution quality even for orders of $ 1M+.

In short, prop AMMs have brought true market making on-chain. They have shown the path forward: a quote-driven, inventory-aware model that, when combined with increasingly sophisticated routing, will define how the Internet Capital Markets vision ultimately comes to fruition.

Over the past year, the role of the DeFi curator, once a niche function in lending markets, has evolved into one of the most systemically important positions in the on-chain economy. Curators now oversee billions in user capital, set risk parameters, design yield strategies, and determine what collateral is considered “safe.”

But DeFi learned an expensive lesson: many curators weren’t actually managing risk; they were cosplaying it.

A Balancer exploit, a cascading stablecoin collapse, and liquidity crises across top vaults forced the industry to confront an uncomfortable truth: the system worked as designed, but the people setting the guardrails did not.

As DeFi evolves, risk management and capital efficiency are becoming modular and specialized functions. A new category of entities, called curators, now design and manage on-chain vaults, marking a major shift in liquidity management since automated market makers. The concept of the curator role was pioneered and formalized by Morpho, which externalized risk management from lending protocols and created an open market for curators specializing in vault strategy and risk optimization. This new standard has since been adopted across DeFi, making curators fundamental for managing vaults and optimizing risk-adjusted returns for depositors.

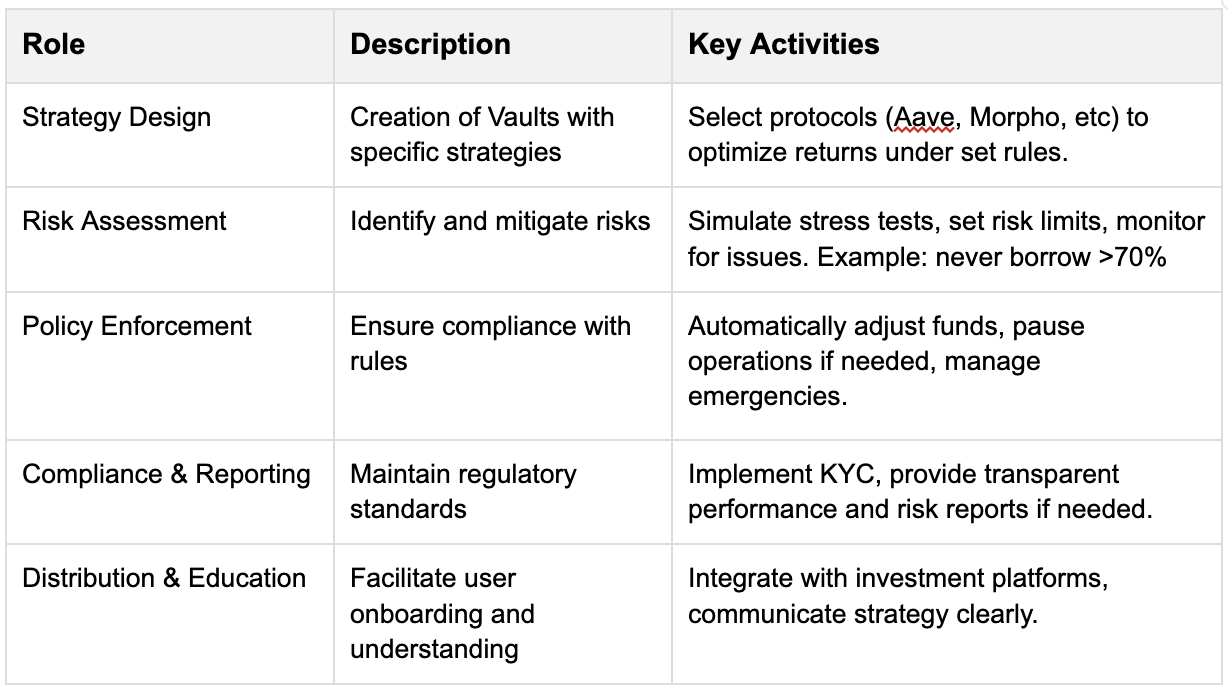

A curator is a trusted, non-custodial strategist who builds, monitors, and optimizes on-chain vaults to deliver risk-adjusted yield for depositors. They design the rules, enforce the limits, and earn performance fees on positive results.

Here’s an overview of the core roles and activities associated with a curator:

The curator market in DeFi has rapidly grown from $300 million to $7 billion in less than a year, reflecting a 2,200% growth. This surge marks a key milestone in the development of risk-managed DeFi infrastructure. The increase is driven by new lending protocols adopting the vault architecture, institutional inflows, the rise of stablecoins, clearer regulations, and growing trust in curators like Stakehouse or Gauntlet.

While we’re still in the “wild west” era of DeFi as recent events have shown, curators are a first step to introduce more isolated and essential risk controls, making on-chain yields more predictable, compliant, and secure for users. This has also enabled companies to introduce “earn”-type of products to their users in a simplified way.

Key metrics:

The business model of DeFi curators is primarily driven by performance fees, earned as a percentage of the yield or profits generated by the vaults they manage. This structure effectively aligns incentives, as curators are rewarded for optimizing returns while maintaining prudent risk management. Curators also work directly with B2B partners in building special-purpose vaults where pricing and revenue share is decided between the participating parties.

Some curators have adopted a 0% performance fee structure on their largest vaults to attract liquidity and strengthen brand recognition (for example, Steakhouse’s USDC vault). Current revenue data available on DeFiLlama provides a good indicator for assessing the earnings and relative performance of active curators.

It began when Balancer v2 stable pools were exploited on November 3, 2025, with a precision rounding bug in the stable swap math that let an attacker drain about 130 million dollars. Seeing a near five year old, heavily audited protocol fail triggered a broad risk reset and reminded everyone that DeFi yield carries real contract risk. Around the same time, Stream Finance disclosed that an external fund manager had lost about 93 million dollars of platform assets. Stream froze deposits, and its staked stablecoin xUSD depegged violently toward 0.30 dollars.

xUSD was widely rehypothecated as collateral. Lenders and stablecoin issuers had lent against it or held it in backing portfolios, in some cases with highly concentrated exposure. When xUSD’s backing came into question, pegs had to be defended, positions were unwound, and exits were gated. What started as a few specific failures became a system wide scramble for liquidity, which is what eventually showed up to users as queues, withdrawal frictions, and elevated rates across curator vaults and lending protocols.

We saw large liquidity crunches on Morpho after the xUSD / Stream Finance blowup. On Morpho, only one of roughly 320 MetaMorpho vaults (MEV Capital's) had direct exposure to xUSD, resulting in about $700,000 in bad debt. However, the shock raised ecosystem-wide risk aversion, with many lenders wanting to withdraw at once.

These liquidity crunches were mainly driven by simultaneous withdrawals colliding with Morpho's isolated-market design. MetaMorpho vaults like Steakhouse USDC aggregate UX, not liquidity. Each vault operates with isolated lending markets and no shared liquidity. Each market has a cap, a LTV limit, and a utilization level that tracks how much cash is already lent out.

When many depositors rushed to withdraw, the only immediately available cash was the idle balance in those specific markets. That idle cash got used up first, utilization hit 100%, and withdrawals moved into a queue. As utilization climbed, the interest rate curve ramped up, spiking as high as 190%, to incentivize borrowers to repay or get liquidated. While that released cash, it doesn't happen instantly. Borrowers need to source funds or liquidations need to clear. Until that flow returns cash to the vault's underlying markets, withdrawals remain slow because there is no shared pool to tap outside the vault's configured markets.

Crucially, even 'safe' USDC vaults without xUSD exposure, like those managed by Steakhouse or Gauntlet briefly became illiquid, out of caution rather than losses. The fragmented liquidity meant funds couldn't be pulled from some global pool, resulting in a classic timing mismatch: immediate redemption demand versus the time needed for borrowers to de-lever and for the vault to pull funds back from its underlying markets. Even so, these vaults recovered within hours, and overall, 80% of withdrawals were completed within three days.

As a random guy on Twitter pointedly said: “It appears that the Celsius/BlockFi’s of this cycle are DeFi protocols lending to vault managers disguised as risk curators”.

The incident demonstrated that Morpho's design worked as intended: isolation contained the damage to one vault, curator decisions limited broader exposure, and the system managed acute stress without breaking. However, it also revealed the tradeoff inherent in the design—localized liquidity can drain quickly even when actual losses are minimal and contained.

Aave and Morpho both enable borrowing and lending, but they differ in how they manage risk and structure their markets.

With Aave, the protocol manages everything: which assets are available, the risk rules, and all market parameters. This makes Aave simple to use. Depositors provide capital to shared pools without making individual risk decisions. This setup ensures deep liquidity, fast borrowing, and broad asset support. However, this “one-size-fits-all” model means everyone shares the same risk. If Aave’s risk management or asset selection fails, all depositors may be affected, and users have limited ability to customize their risk exposure.

Morpho, on the other hand, decentralizes risk management by allowing independent curators (like Gauntlet or Steakhouse) to create specialized vaults. Each vault has its own risk parameters, such as different collateral requirements, liquidity limits, or liquidation rules. Lenders and borrowers choose which vaults to use based on their risk appetite. This provides much more flexibility, allowing users to select safer or riskier strategies.

However, this flexibility also leads to fragmented liquidity. Funds are spread across many vaults, and users must evaluate each vault’s risks before participating. For non-experts, this can be challenging, and it can occasionally result in lower liquidity or slower withdrawals during volatile market conditions.

While the Balancer hack is out of the control of any curator and was hard to foresee, xUSD is a different story. Basic risk hygiene would have gone a long way. If curators had treated xUSD as a risky credit instrument rather than “dollar-equivalent collateral,” most of the bad debt, queues, and forced deleveraging would have been materially smaller. Curators need to step their game up and there is a lot of room for improvement…

Over the coming years, resolving gaps in regulatory clarity, risk metrics, distribution access, and technical interoperability will transform curators from crypto-native specialists into fully licensed, ratings-driven infrastructure that channels institutional capital into on-chain yield with similar standards and scale of traditional asset managers.

The curator market currently operates in a regulatory grey area. Curators do not hold assets or control capital directly, but their work (configuring vaults and tracking performance) closely resembles activities of regulated investment firms/advisors. At the moment, none of the major curators are licensed. Yet to serve banks and RIAs, curators will need investment advisor registration, KYC capabilities, and institutional custody integration—the compliance stack that crypto-native players deliberately avoid. However, the market is slowly moving toward regulated infrastructure, as shown by Steakhouse’s partnership with Coinbase Institutional, the tokenized Treasury efforts of Ondo and Superstate or Société Générale announcing depositing into a Morpho. Under current U.S. and EU rules, curators who earn performance fees or promote yield-generating products may eventually fall under investment advisory regulations. This creates both a compliance risk and a first-mover opportunity: a regulated curator could define new governance standards, attract institutional investors, and speed up the market’s formalization.

One gap in the DeFi curator market is the absence of a standardized risk taxonomy. Today, every curator invents its own subjective labels: “Prime”, “Core”, “High-Yield” or “Aggressive” with no shared definitions, no comparable metrics, and no regulatory acceptance. There have been attempts by a number of players, such as Exponential, Credora (acquired by Restone), and Synnax, to create a unified standard for risk ratings, but no universal standard has been accepted by the space yet. This fragmentation blocks advisors from building compliant portfolios and prevents institutions from scaling allocations. In traditional finance, the Big 3 credit rating agencies (Moody’s, S&P, Fitch) generate over $6 billion annually by applying universal, transparent ratings to $60 trillion in debt. DeFi needs the same: AAA/BBB ratings with hard rules on parameters such as collateral types, oracle design, initial and liquidatable LTVs, and liquidity thresholds. Without it, curated TVL stays siloed and institutional inflows can remain limited. The first player to deliver a Moody’s-grade rating with Standard labels, Transparent methodology and Regulatory acceptance has the opportunity to own the category and unlock the next $100 billion in advisor-driven deposits.

The market is still bottlenecked by crypto-native brands. Curators like Steakhouse and MEV Capital dominate TVL with battle-tested strategies, but they lack the institutional credibility, regulatory wrappers, and advisor relationships that RIAs and private banks demand. This leaves billions in potential deposits stranded in wallets or CEXs, unable to flow seamlessly into curated vaults. In TradFi, asset managers like BlackRock route trillions through established RIA platforms, wealth desks, and brokerage channels. DeFi has not a lot of equivalents yet: The Coinbase x Morpho cbBTC partnership is the exception proving the rule, and shows early promising signs that with sufficient track record and credibility, institutions and platforms with distribution are willing to tap into DeFi-native strategies. When infrastructure connects, billions flow. We need more of it. Custodian APIs that let advisors allocate client funds on-chain, wealth platform integrations, etc. Société Générale's digital asset arm, SG-FORGE, selected Morpho specifically because its architecture solves the problem of finding a regulated, compliant counterparty for on-chain activities. The curator who can build the "click-through" infrastructure that turns any compliant vault into an advisor-native product will unlock the next $50 billion in institutional AUM.

DeFi curators face major technical fragmentation. Each platform (such as Morpho or Kamino) requires its own custom code, dashboards, and monitoring tools. Managing a single vault across multiple platforms means rebuilding everything from scratch, much like opening separate bank accounts with no shared infrastructure. This slows growth, increases costs, and limits scale. What's missing: one system to configure all vaults. Set position limits once, deploy to Morpho and Kamino automatically. Build for one platform, launch on ten. What the market needs is a unified engine that works across all platforms: configure it once, apply consistent rules, and manage every vault through the same system.

The recent failures proved two things simultaneously:

If curators want to handle institutional capital, they must evolve from clever yield optimizers into true risk managers with:

The next $50–$100B of on-chain yield will flow to curators who look less like DeFi power users and more like regulated asset managers. Conservative risk frameworks. Scalable distribution. Institutional compliance.

The curator role isn't disappearing. It's professionalizing.

The race to define that standard starts now.

The analysis focuses on evaluating the impact of Double Zero on Solana’s performance across three layers — gossip latency, block propagation, and block rewards.

shred_insert_is_full logs, block arrival times through DZ were initially delayed compared to the public Internet, but the gap narrowed over time.DoubleZero (DZ), is a purpose-built network underlay for distributed systems that routes consensus-critical traffic over a coordinated fiber backbone rather than the public Internet. The project positions itself as a routing, and policy controls tailored to validators and other latency-sensitive nodes. In practical terms, it provides operators with tunneled connectivity and a separate addressing plane, aiming to cut latency and jitter, smooth bandwidth, and harden nodes against volumetric noise and targeted attacks.

The design goal is straightforward, albeit ambitious: move the heaviest, most timing-sensitive parts of blockchain networking onto dedicated fiber-optic and subsea cables. In DoubleZero’s framing, that means prioritizing block propagation and transaction ingress, reducing cross-continent tail latency, and stripping malformed or spammy traffic before it hits validator sockets.

Solana’s throughput is gated as much by network effects as by execution, so any reduction in leader-to-replica and replica-to-leader propagation delays can translate into higher usable TPS. Overall, DoubleZero expects real-world performance on mainnet to improve substantially as the network is adopted by the validator cluster. Reducing latency by up to 100ms (including zero jitter) along some routes, and increasing bandwidth available to the average Solana validator tenfold.

In this article, we evaluate the effects of DoubleZero on the Solana network by comparing its performance with that of the public Internet. We measure how the use of DZ influences network latency, throughput, and block propagation efficiency, and we assess if these network-level changes translate into differences in slot extracted value.

Solana validators natively report gossip-layer round-trip time (RTT) through periodic ping–pong messages exchanged among peers. These measurements are logged automatically by the validator process and provide a direct view of peer-to-peer latency at the protocol level, as implemented in the Agave codebase.

To assess the impact of DoubleZero, we analyzed these validator logs rather than introducing any external instrumentation. Two machines with identical hardware and network conditions, co-located were used. We refer to them as Identity 1 and Identity 2 throughout the analysis.

In addition to gossip-layer RTT, we also examined block propagation time, which represents the delay between when a block is produced by the leader and when it becomes fully available to a replica. For this, we relied on the shred_insert_is_full log event emitted by the validator whenever all shreds of a block have been received and the block can be reconstructed locally. This event provides a precise and consistent timestamp for block arrival across validators, enabling a direct comparison of propagation delays between the two identities.

We chose shred_insert_is_full instead of the more common bank_frozen event because the latter only helps in defining the jitter. A detailed discussion of this choice is provided in the Appendix.

The experiment was conducted across seven time windows:

This alternating setup enables us to disentangle two sources of variation: intrinsic differences due to hardware, time-of-day, and network conditions, and the specific effects introduced by routing one validator through DZ. The resulting RTT distributions offer a direct measure of how DoubleZero influences gossip-layer latency within the Solana network.

This section examines how Double Zero influences the Solana network at three complementary levels: peer-to-peer latency, block propagation, and validator block rewards. We first analyze changes in gossip-layer RTT to quantify DZ’s direct impact on communication efficiency between validators. We then study block propagation times derived from the shred_insert_is_full event to assess how modified RTTs affects block dissemination. Finally, we investigate fee distributions to determine whether DZ yield measurable differences in extracted value (EV) across slots. Together, these analyses connect the network-level effects of DZ to their observable consequences on Solana’s operational and economic performance.

The gossip layer in Solana functions as the control plane: it handles peer discovery, contact-information exchange, status updates (e.g., ledger height, node health) and certain metadata needed for the data plane to operate efficiently. Thus, by monitoring RTT in the gossip layer we are capturing a meaningful proxy of end-to-end peer connectivity, latency variability, and the general health of validator interconnectivity. Since the effectiveness of the data plane (block propagation, transaction forwarding) depends fundamentally on the control-plane’s ability to keep peers informed and connected, any reduction in gossip-layer latency can plausibly contribute to faster, more deterministic propagation of blocks or shreds.

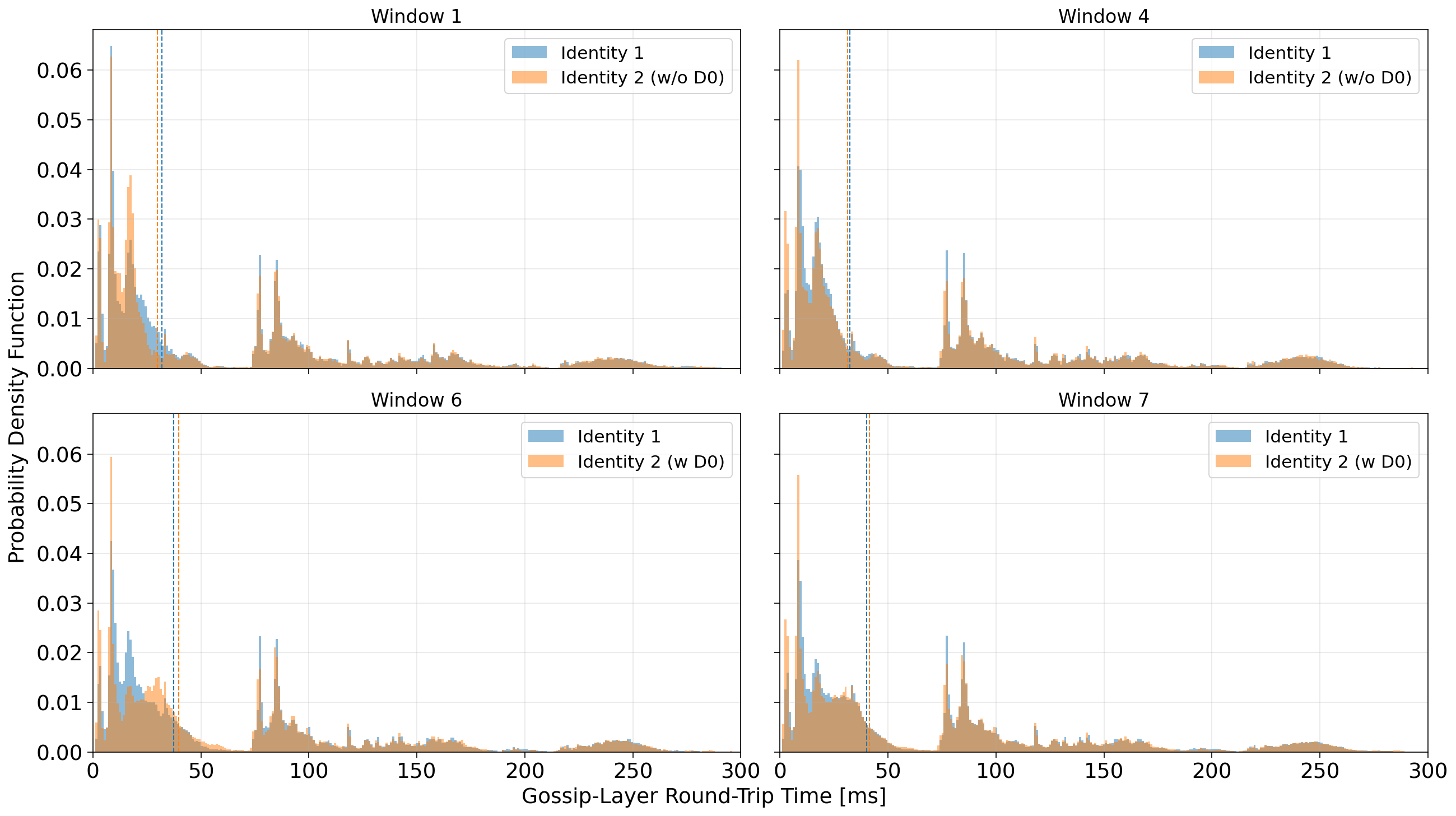

In Figure 1, we present the empirical probability density functions (PDFs) of gossip-layer round-trip time (RTT) from our two identities under different experimental windows.

Across all windows, the RTT distributions are multimodal, which is expected in Solana’s gossip layer given its geographically diverse network topology. The dominant mode below 20–30 ms likely corresponds to peers located in the same region or data center, while the secondary peaks around 80–120 ms and 200–250 ms reflect transcontinental routes (for instance, between North America and Europe or Asia).

In Windows 1 and 4, when both validators used the public Internet, the RTT distributions for Identity 1 and Identity 2 largely overlap. Their medians mostly coincide, and the overall shape of the distribution is very similar, confirming that the two machines experience comparable baseline conditions and that intrinsic hardware or routing differences are negligible.

A mild divergence appears in Windows 6 and 7, when Identity 2 is connected through DZ. The median RTT of Identity 2 shifts slightly to the right, indicating a small increase in the typical round-trip time relative to the public Internet baseline. This shift is primarily driven by a dilution of the fast peer group: the density of peers within the 10–20 ms range decreases, while that population redistributes toward higher latency values, up to about 50–70 ms. For longer-distance modes (around 80–100 ms and beyond) it seems the RTT is largely unaffected.

Overall, rather than a uniform improvement, these distributions suggest that DZ introduces a small increase in gossip-layer latency for nearby peers, possibly reflecting the additional routing path through the DZ tunnel.

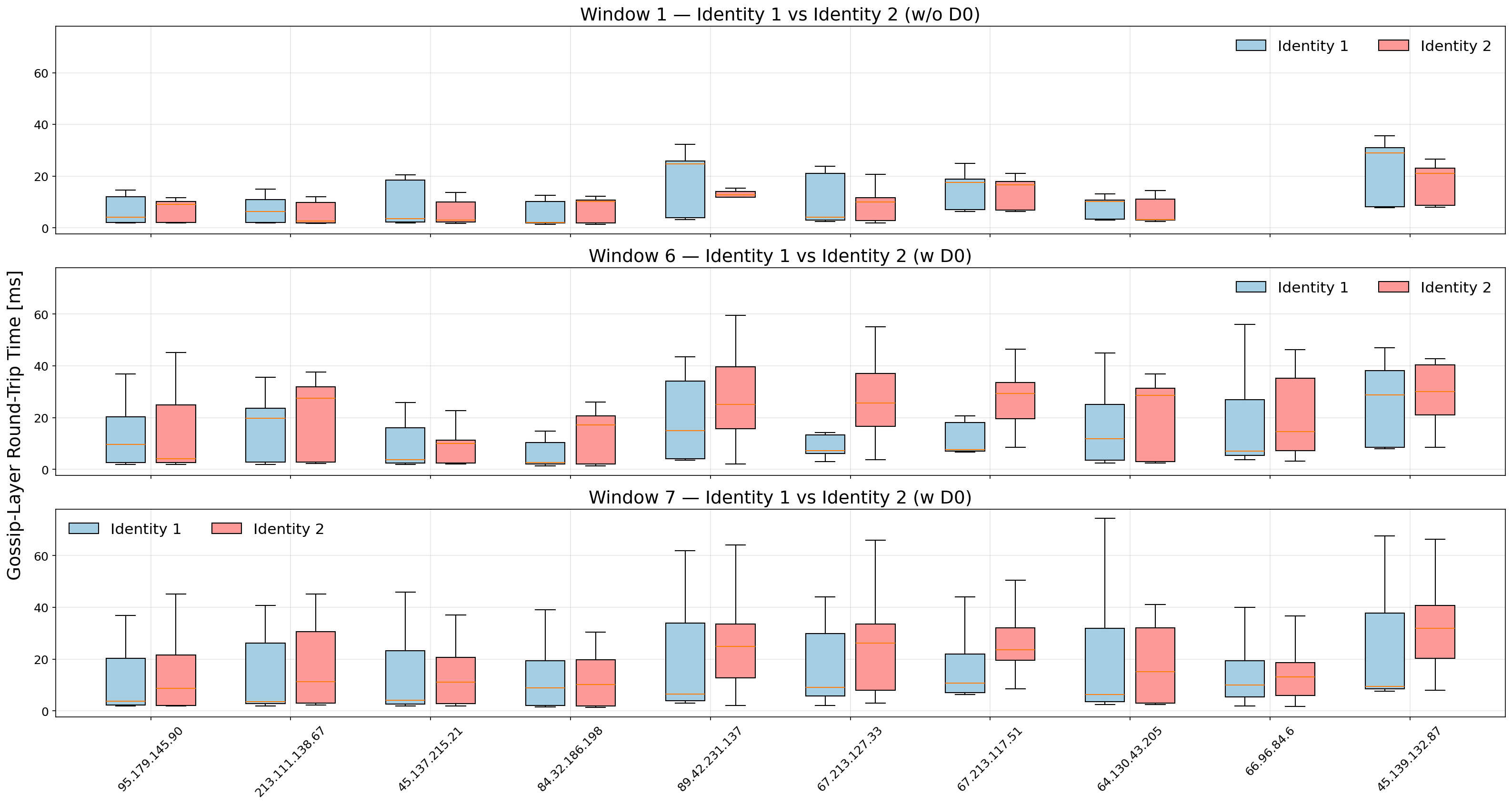

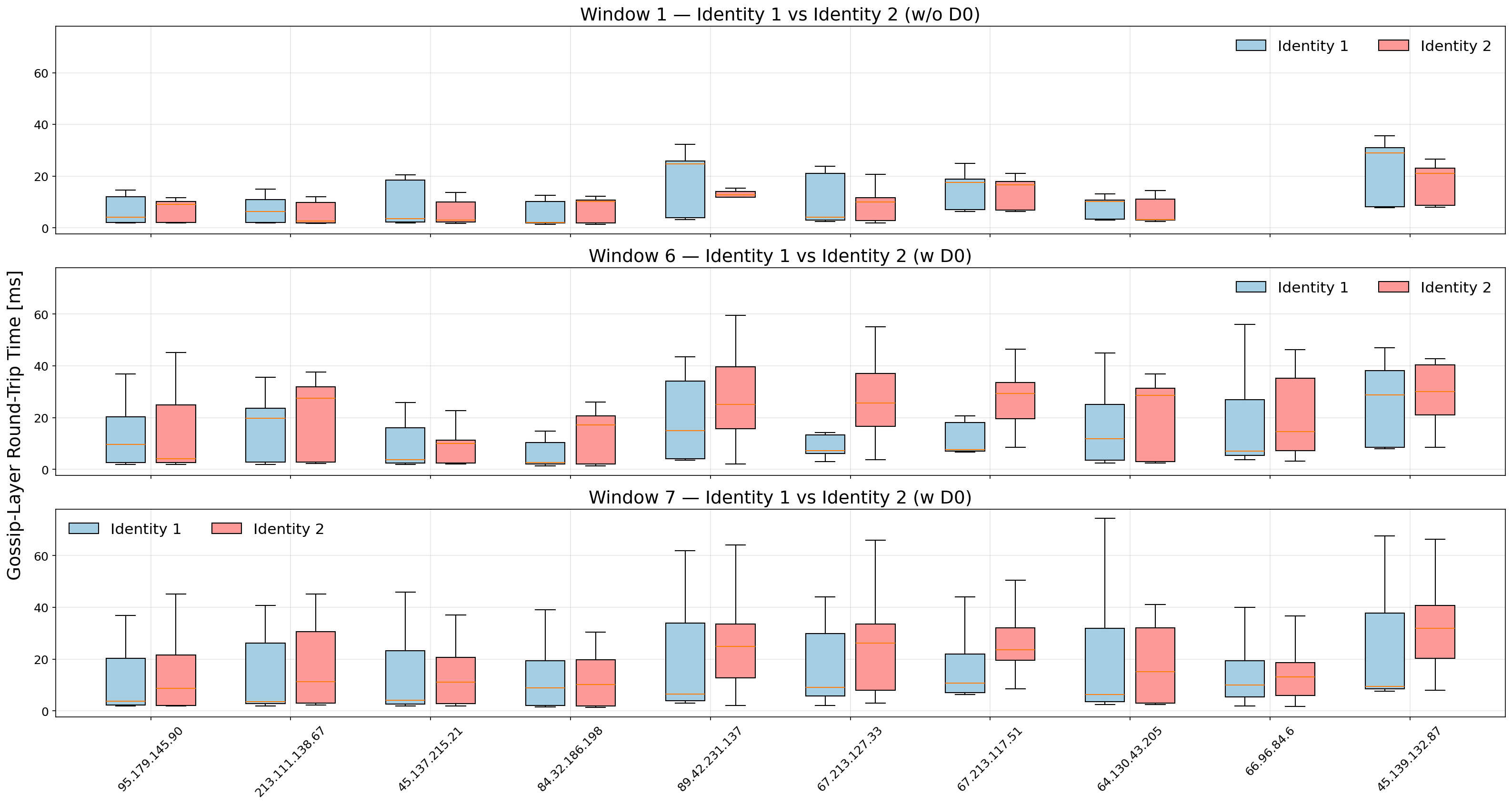

When focusing exclusively on validator peers, the distributions confirm the effect of DZ on nearby peers (below 50 ms). However, a clearer pattern emerges for distant peers—those with RTTs exceeding roughly 70–80 ms. In Windows 6 and 7, where Identity 2 is connected through DZ, the peaks in the right tail of the PDF shifts to te left, signaling a modest but consistent reduction in latency for long-haul validator connections.

Despite this gain, the behaviour of median RTT remains almost unaffected: it increases when connecting to DoubleZero. Most validators are located within Europe, so the aggregate distribution is dominated by short- and mid-range connections. Consequently, while DZ reduces latency for a subset of geographically distant peers, this improvement is insufficient to significantly shift the global RTT distribution’s central tendency.

In order to better visualize the effect highlighted from Fig. 2, we can focus on individual validator peers located within the 60 ms latency range, see Fig. 3. These results confirm that the modest rightward shift observed in the aggregate distributions originates primarily from local peers, whose previously low latencies increase slightly when routed through DZ. For example, the peer 67.213.127.33 (Amsterdam) moves from a median RTT below 10 ms in the baseline window to above 20 ms under DZ. Similar, though less pronounced, upward shifts occur for several other nearby peers.

For distant validators, the introduction of DoubleZero systematically shifts the median RTT downward, see Fig. 4. This improvement is especially evident for peers such as 15.235.232.142 (Singapore), where the entire RTT distribution is displaced toward lower values and the upper whiskers contract, suggesting reduced latency variance. The narrowing of the boxes in many cases further implies improved consistency in round-trip timing.

Taken together, these results confirm that DZ preferentially benefits geographically distant peers, where conventional Internet routing is less deterministic and often suboptimal. The impact, while moderate in absolute terms, is robust across peers and windows, highlighting DZ’s potential to improve inter-regional validator connectivity without increasing jitter.

Overall, these results capture a snapshot of Double Zero’s early-stage performance. As we will show in the next subsection, the network has improved markedly since its mainnet launch. A comparison of MTR tests performed on October 9 and October 18 highlights this evolution. Initially, routes between Amsterdam nodes (79.127.239.81 → 38.244.189.101) involved up to seven intermediate hops with average RTTs around 24 ms, while the Amsterdam–Frankfurt route (79.127.239.81 → 64.130.57.216) exhibited roughly 29 ms latency and a similar hop count. By mid-October, both paths had converged to two to three hops, with RTTs reduced to ~2 ms for intra-Amsterdam traffic and ~7 ms for Amsterdam–Frankfurt. This reduction in hop count and latency demonstrates tangible routing optimization within the DZ backbone, suggesting that path consolidation and improved internal peering have already translated into lower physical latency.

In Solana, the time required to receive all shreds of a block offers a precise and meaningful proxy for block propagation time. Each block is fragmented into multiple shreds, which are transmitted through the Turbine protocol, a tree-based broadcast mechanism designed to efficiently distribute data across the validator network. When a validator logs the shred_insert_is_full event, it indicates that all expected shreds for a given slot have been received and reassembled, marking the earliest possible moment at which the full block is locally available for verification. This timestamp therefore captures the network component of block latency, isolated from execution or banking delays.

However, the measure also reflects the validator’s position within Turbine’s dissemination tree. Nodes closer to the root—typically geographically or topologically closer to the leader—receive shreds earlier, while those situated deeper in the tree experience higher cumulative delays, as each hop relays shreds further downstream. This implies that differences in block arrival time across validators are not solely due to physical or routing latency, but also to the validator’s assigned role within Turbine’s broadcast hierarchy. Consequently, block arrival time must be interpreted as a convolution of propagation topology and network transport performance.

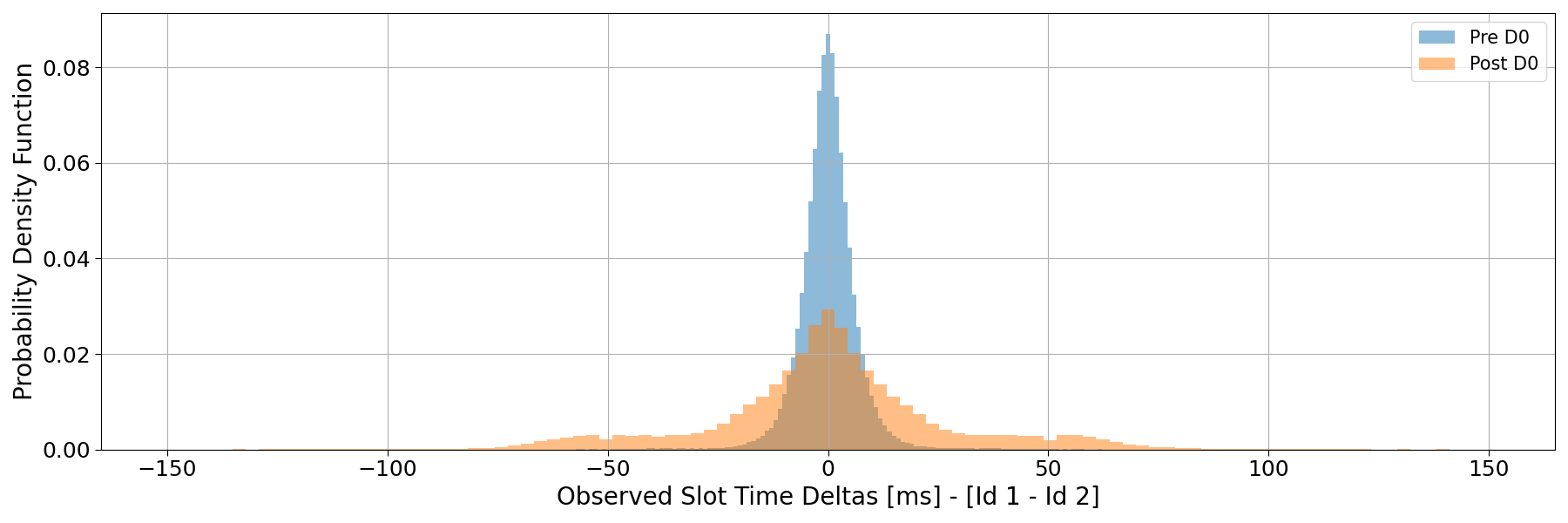

The figure below presents the empirical probability density functions (PDFs) of latency differences between our two validators, measured as the time difference between the shred_insert_is_full events for the same slot. Positive values correspond to blocks arriving later at Identity 2 (the validator connected through Double Zero).

In the early windows (2 and 3), when Double Zero was first deployed, the distribution exhibits a pronounced right tail, indicating that blocks frequently arrived substantially later at the DZ-connected validator. This confirms that during the initial deployment phase, DZ added a measurable delay to block dissemination, consistent with the higher peer latency observed in the gossip-layer analysis.

Over time, however, the situation improved markedly. In windows 5–7, the right tail becomes much shorter, and the bulk of the distribution moves closer to zero, showing that block arrival delays through DZ decreased substantially. Yet, even in the most recent window, the distribution remains slightly right-skewed, meaning that blocks still tend to reach the DZ-connected validator marginally later than the one on the public Internet.

This residual offset is best explained by the interaction between stake distribution and Turbine’s hierarchical structure. In Solana, a validator’s likelihood of occupying an upper position in the Turbine broadcast tree increases with its stake weight. Since the majority of Solana’s stake is concentrated in Europe, European validators are frequently placed near the top of the dissemination tree, receiving shreds directly from the leader or after only a few hops. When a validator connects through Double Zero (DZ), however, we have seen that EU–EU latency increases slightly compared to the public Internet. As a result, even if the DZ-connected validator occupies a similar topological position in Turbine, the added transport latency in the local peer group directly translates into slower block arrival times. Therefore, the persistent right-skew observed in the distribution is primarily driven by the combination of regional stake concentration and the modest latency overhead introduced by DZ in short-range European connections, rather than by a deeper tree position or structural topology change.

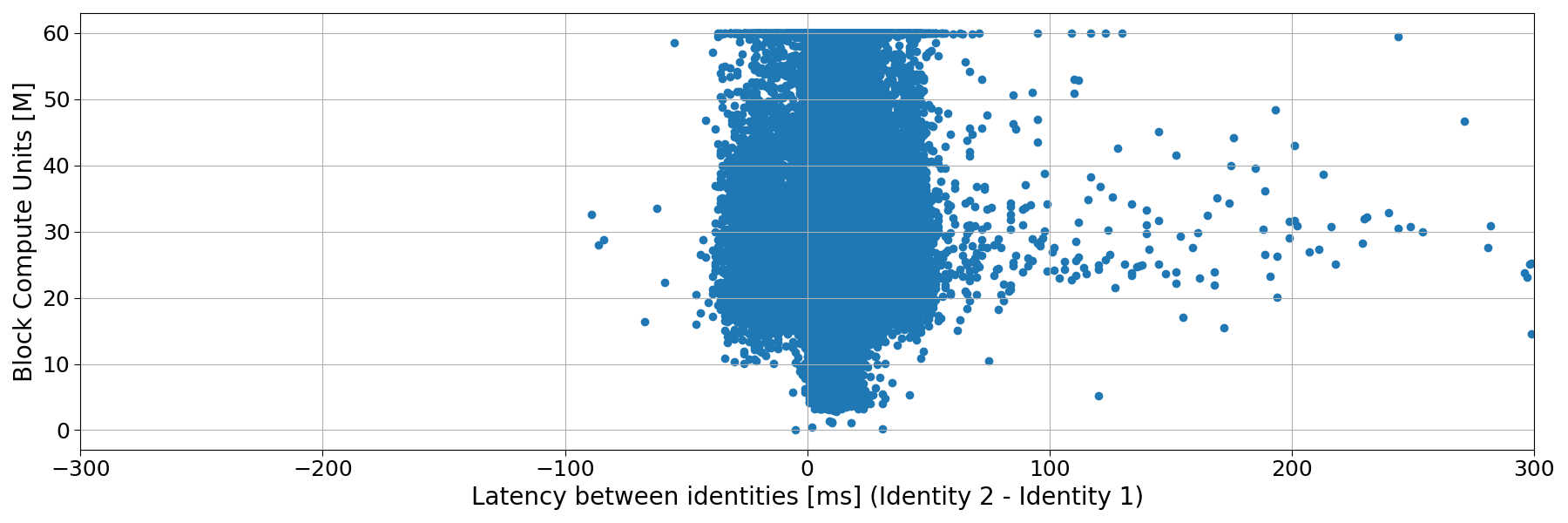

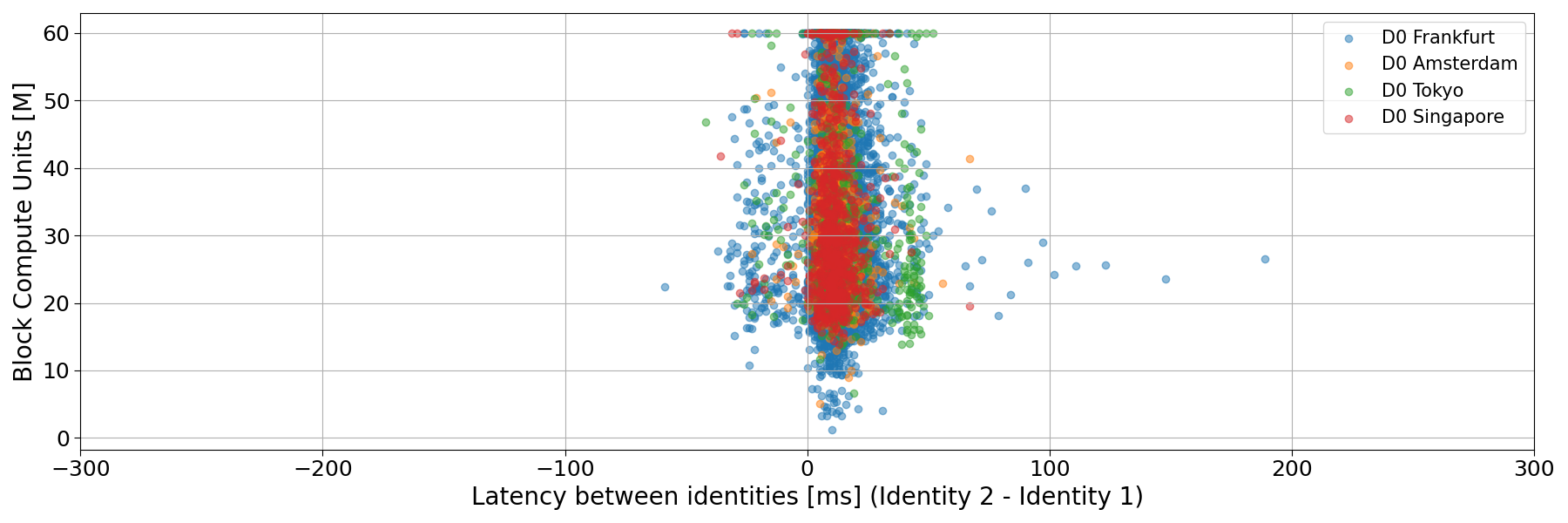

To further assess the geographical component of Double Zero’s (DZ) impact, we isolated slots proposed by leaders connected through DZ and grouped them by leader region. For leaders located in more distant regions such as Tokyo, DZ provides a clear advantage: the latency difference between identities shifts leftward, indicating that blocks from those regions are received faster through DZ. Hence, DZ currently behaves as a latency equalizer, narrowing regional disparities in block dissemination rather than uniformly improving performance across all geographies.

Finally, we see no correlation between block size (in terms of Compute Units) and propagation time.

It has been demonstrated that timing advantages can directly affect validator block rewards on Solana, as shown in prior research. However, in our view, this phenomenon does not translate into an organic, system-wide improvement simply by reducing latency at the transport layer. The benefit of marginal latency reduction is currently concentrated among a few highly optimized validators capable of exploiting timing asymmetries through sophisticated scheduling or transaction ordering strategies. In the absence of open coordination mechanisms—such as a block marketplace or latency-aware relay layer—the overall efficiency gain remains private rather than collective, potentially reinforcing disparities instead of reducing them.

Since any network perturbation can in principle alter the outcome of block rewards, we tested the specific effect of DoubleZero on extracted value (EV). Building on the previously observed changes in block dissemination latency, we examined whether routing through DZ produces measurable differences in block EV—that is, whether modifying the underlying transport layer influences the value distribution of successfully produced slots.

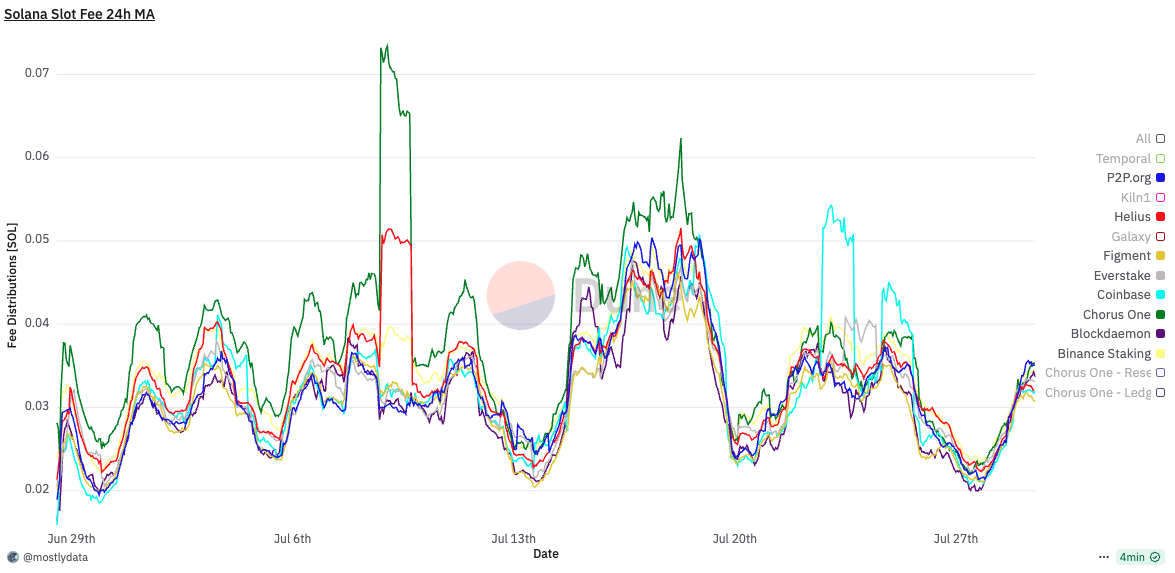

Figure 9 compares validators connected through DoubleZero with other validators in terms of block fees, used here as a proxy for extracted value (EV). Each line represents a 24-hour sliding window average, while shaded regions correspond to the 5th–95th percentile range. Dashed lines on the secondary axis show the sample size over time.

Before October 9, DZ-connected validators exhibit a slightly higher mean and upper percentile (p95) for block fees, together with larger fluctuations, suggesting sporadic higher-value blocks. During the market crash period (October 10–11), this difference becomes temporarily more pronounced: the mean block fee for DZ-connected validators exceeds that of others, with the p95 moving widely above. After October 11, this pattern disappears, and both groups show virtually identical distributions.

To verify whether the pre–October 9 difference and the market crash upside movement reflected a real effect or a statistical artifact, we applied a permutation test on the average block fee, cfr. Dune queries 5998293 and 6004753. This non-parametric approach evaluates the likelihood of observing a mean difference purely by chance: it repeatedly shuffles the DZ and non-DZ labels between samples, recalculating the difference each time to build a reference distribution under the null hypothesis of no effect.

The resulting mean block fee delta of 0.00043 SOL with p-value of 0.1508 during the period pre–October 9 indicates that the observed difference lies well within the range expected from random sampling. In other words, the apparent gain is not statistically meaningful and is consistent with sample variance rather than a causal improvement due to DZ connectivity. When restricting the analysis to the market crash period (October 10–11), the difference in mean extracted value (EV) between DZ-connected and other validators becomes more pronounced. In this interval, the mean block fee delta rises to $\sim$ 0.00499 SOL, with a corresponding p-value of 0.0559. This borderline significance suggests that under high-volatility conditions—when order flow and transaction competition intensify—reduced latency on long-haul routes may temporarily yield measurable EV gains.

However, given the limited sample size and the proximity of the p-value to the 0.05 threshold, this result should be interpreted cautiously: it may reflect short-term network dynamics rather than a persistent causal effect. Further tests across different volatility regimes are needed to confirm whether such transient advantages recur systematically.

This study assessed the effects of Double Zero on the Solana network through a multi-layer analysis encompassing gossip-layer latency, block dissemination time, and block rewards.

At the network layer, Solana’s native gossip logs revealed that connecting a validator through DZ introduces an increase in round-trip time among geographically close peers within Europe, while simultaneously reducing RTT for distant peers (e.g., intercontinental connections such as Europe–Asia). This pattern indicates that DZ acts as a latency equalizer, slightly worsening already short paths but improving long-haul ones. Over time, as the network matured, overall latency performance improved. Independent MTR measurements confirmed this evolution, showing a sharp reduction in hop count and end-to-end delay between October 9 and October 18, consistent with substantial optimization of the DZ backbone.

At the propagation layer, analysis of shred_insert_is_full events showed that the time required to receive all shreds of a block — a proxy for block dissemination latency — improved over time as DZ routing stabilized. Early measurements exhibited longer block arrival times for the DZ-connected validator, while later windows showed a markedly narrower latency gap. Nevertheless, blocks still arrived slightly later through DZ, consistent with Solana’s Turbine topology and stake distribution: since most high-stake validators are located in Europe and thus likely occupy upper levels in Turbine’s broadcast tree, even small EU–EU latency increases can amplify downstream propagation delays.

At the economic layer, we examined block fee distributions as a proxy for extracted value (EV). DZ-connected validators displayed slightly higher 24-hour average and upper-percentile fees before October 10, but this difference disappeared thereafter. A permutation test on pre–October 10 data confirmed that the apparent advantage is not statistically significant, and therefore consistent with random variation rather than a systematic performance gain.

Overall, the evidence suggests that DZ’s integration introduces mild overhead in local connections but provided measurable improvement for distant peers, particularly in intercontinental propagation. While these routing optimizations enhance global network uniformity, their economic impact remains negligible at the current adoption level.

A natural candidate for measuring block arrival time in Solana is the bank_frozen log event, which marks the moment when a validator completely recover a block in a given bank. However, this signal introduces a strong measurement bias that prevents it from being used to infer true block propagation latency.

The bank_frozen event timestamp is generated locally by each validator, after all shreds have been received, reconstructed, and the bank has been executed. Consequently, the recorded time includes not only the network component (arrival of shreds) but also:

When comparing bank_frozen timestamps across validators, these effects dominate, producing a stationary random variable with zero mean and a standard deviation equal to the system jitter. This means that timestamp differences reflect internal timing noise rather than propagation delay.

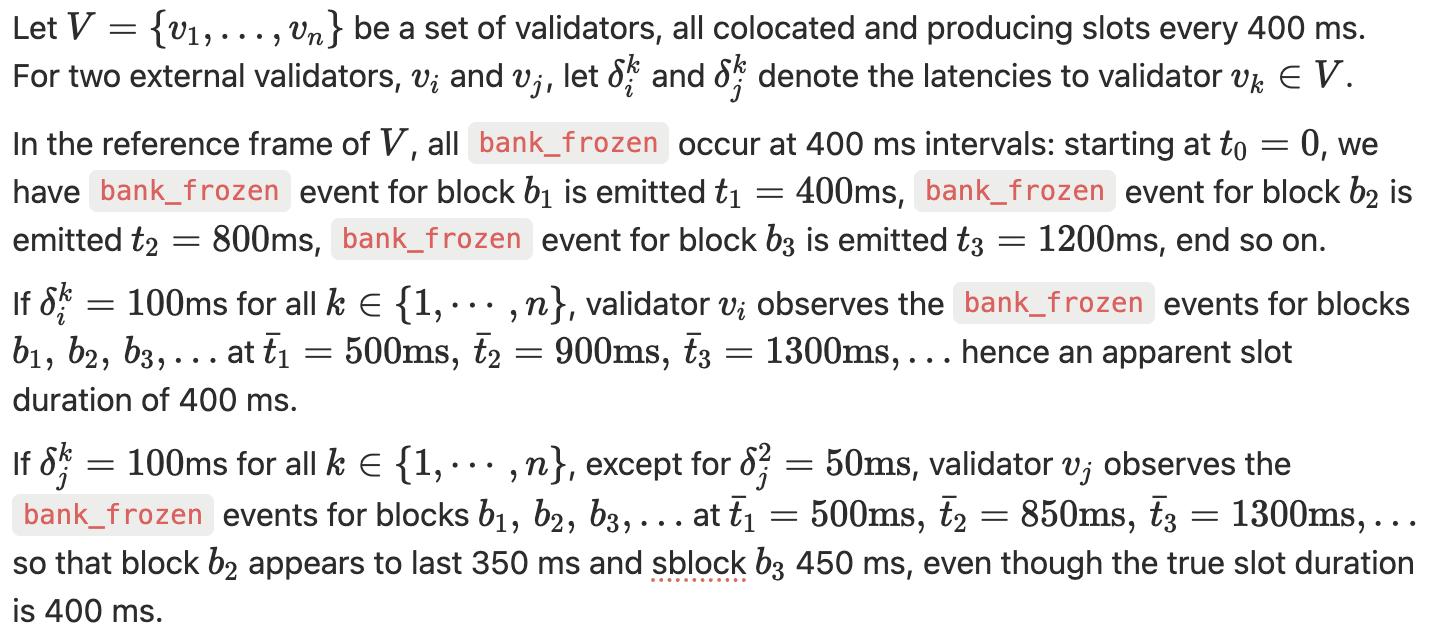

Consider the following illustrative example.

In general, a local measurement for block time extracted from the bank_frozen event can be parametrized as

The figure below shows the distribution of time differences between bank_frozen events registered for the same slots across the two identities. As expected, the distribution is nearly symmetric around zero, confirming that the observed variation reflects only measurement jitter rather than directional latency differences.

A direct implication of this behaviour is the presence of an intrinsic bias in block time measurements as reported by several community dashboards. Many public tools derive slot times from the timestamp difference between consecutive bank_frozen events, thereby inheriting the same structural noise described above.

For instance, the Solana Compass dashboard reports a block time of 903.45 ms for slot 373928520. When computed directly from local logs, the corresponding bank_frozen timestamps yield 918 ms, whereas using the shred_insert_is_full events — which capture the completion of shred reception and exclude execution jitter — gives a more accurate value of 853 ms.

Similarly, for slot 373928536, the dashboard reports 419 ms, while the shred_insert_is_full–based estimate is 349 ms.

Blockchains are built to ensure both liveness and safety by incentivizing honest participation in the consensus process. However, most known consensus implementations are not fully robust against external economic incentives. While the overall behaviour tends to align with protocol expectations, certain conditions create incentives to deviate from the intended design. These deviations often exploit inefficiencies or blind spots in the consensus rules. When such actions degrade the protocol's overall performance, the protocol design needs to be fixed, otherwise people will simply keep exploiting these weaknesses.

In a world where data is the new oil, every millisecond has value. Information is converted into tangible gains by intelligent agents, and blockchain systems are no exception. This dynamic illustrates how time can be monetized. In Proof-of-Stake (PoS) systems, where block rewards are not uniformly distributed among participants, the link between time and value can create incentives for node operators to delay block production, effectively "exchanging time for a better evaluation." This behaviour stems from rewards not being shared. A straightforward solution would be to pool rewards and redistribute them proportionally, based on stake and network performance. Such a mechanism would eliminate the incentive to delay, unless all nodes collude, as any additional gains would be diluted across the network.

In this analysis, we evaluate the cost of time on Solana from both the operator’s and the network’s perspective.

It wasn’t long ago—May 31st, 2024—when Anatoly Yakovenko, in a Bankless episode, argued that timing games on Solana were unfeasible due to insufficient incentives for node operators. However, our recent tests indicate that, in practice, node operators are increasingly compelled to engage in latency optimization as a strategic necessity. As more operators exploit these inefficiencies, they raise the benchmark for expected returns, offering capital allocators a clear heuristic: prioritize latency-optimized setups. This dynamic reinforces itself, gradually institutionalizing the latency race as standard practice and pressuring reluctant operators to adapt or fall behind. The result is an environment where competitive advantage is no longer defined by protocol alignment, but by one’s readiness to exploit a persistent structural inefficiency. A similar dynamic is observed on Ethereum, see e.g. The cost of artificial latency in the PBS context, but on Solana the effect may be magnified due to its high-frequency architecture and tight block production schedule.

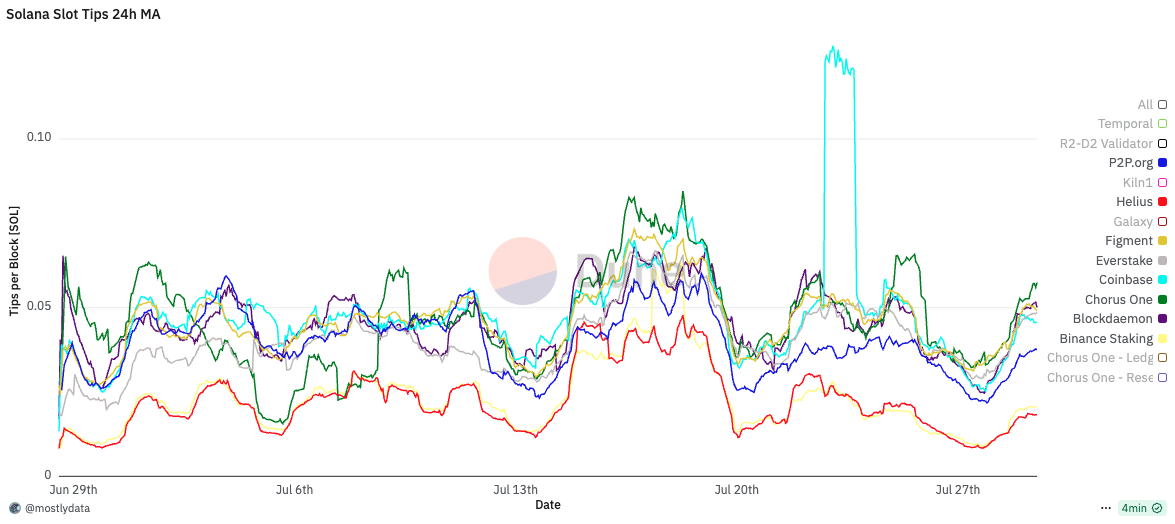

To test this hypothesis, we artificially introduced a delay of approximately 100ms in our slot timing (giving us an average slot time of 480ms) from June 25th to July 20th. The experiment was structured in distinct phases:

The decision to degrade bundle performance from July 2nd to July 10th was motivated by the strong correlation between fees and tips, which made it difficult to determine whether the observed effects of delay were attributable solely to bundle processing or to overall transaction execution. Data can be checked via our Dune dashboard here.

Analyzing the 24-hour moving average distribution of fees per block, we observe a consistent increase of approximately 0.005 SOL per block, regardless of bundle usage - we only observed a small relative difference compared to the case of optimized bundles. For a validator holding 0.2% of the stake, and assuming 432,000 slots per epoch, this translates to roughly 4.32 SOL per epoch, or about 790 SOL annually.

When MEV is factored in, the average fee difference per block increases by an additional 0.01 SOL. Due to the long-tailed distribution of MEV opportunities, this difference can spike up to 0.02 SOL per block, depending on market conditions. Interestingly, during periods of artificially low bundle usage, fees and tips begin to decouple, tips revert to baseline levels even under timing game conditions. This suggests that optimization alone remains a significant driver of performance.

However, as Justin Drake noted, when the ratio of ping time to block time approaches one, excessive optimization may become counterproductive. A striking example of this is Helius: despite being one of the fastest validators on Solana, it consistently ranks among the lowest in MEV rewards. This mirrors findings on Ethereum, where relays deliberately reduce optimization to preserve a few additional milliseconds for value extraction.

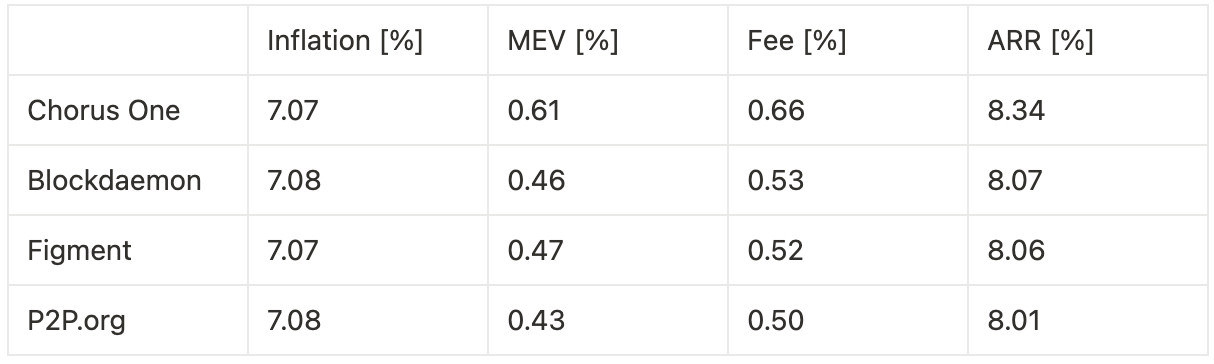

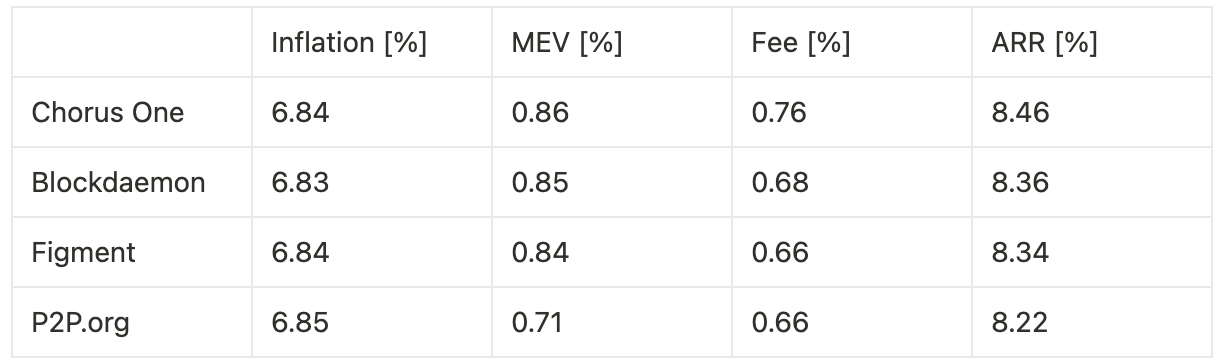

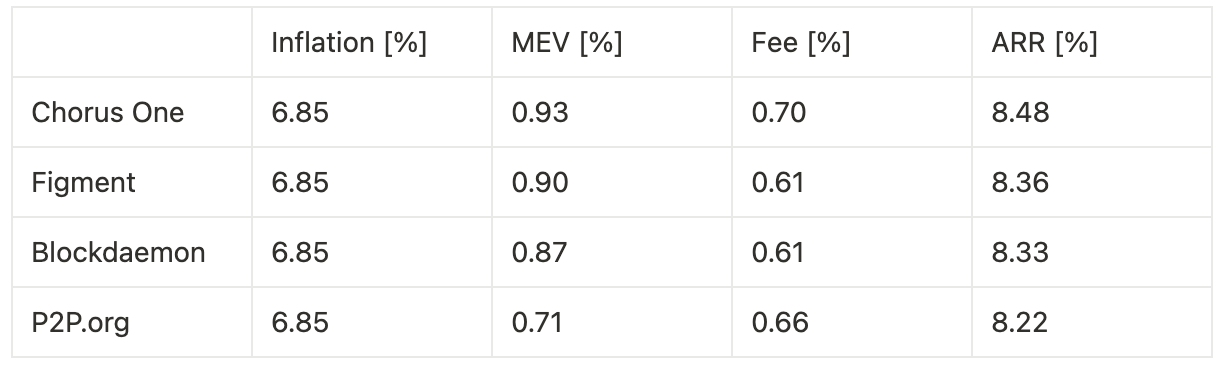

Extrapolating annualized returns across the three experimental phases—benchmarking against other institutional staking providers—we observe the following:

Timing games combined with optimization yield a 24.5% increase in fees and a 32.6% increase in MEV, resulting in an overall 3.0% uplift in total rewards, corresponding to a 27 basis point improvement in annualized return.

Timing games without bundle optimization lead to a 10.0% increase in fees, translating to an 8 basis point gain in annualized return.

Optimization without timing games produces a 3.3% increase in MEV and a 14.7% increase in fees, for a combined 1.4% boost in total rewards, or 12 basis points on annualized return.

Our analysis demonstrates that both timing games and latency optimization materially impact validator rewards on Solana. When combined, they produce the highest yield uplift—up to 3.0% in total rewards, or 27 basis points annually—primarily through increased MEV extraction and improved fee capture. However, even when used independently, both techniques deliver measurable gains. Timing games alone, without bundle optimization, still provide an 8 basis point boost, while pure optimization yields a 12 basis point increase.

These results challenge prior assumptions that the incentives on Solana are insufficient to support timing-based strategies. In practice, latency engineering and strategic delay introduce nontrivial financial advantages, creating a competitive feedback loop among operators. The stronger the economic signal, the more likely it is that latency-sensitive infrastructure becomes the norm.

Our findings point to a structural inefficiency in the protocol design. Individual actors, with rational behaviour under existing incentives, will always try to exploit these inefficiencies. We think that, the attention should be directed toward redesigning reward mechanisms—e.g., through pooling or redistribution—to neutralize these dynamics. Otherwise, the network risks entrenching latency races as a defining feature of validator competition, with long-term consequences for decentralization and fairness.

In this section, we classify and quantify the main effects that arise from engaging in timing games. We identify four primary impact areas: (1) inflation rewards, (2) transactions per second (TPS), (3) compute unit (CU) usage per block, and (4) downstream costs imposed on the leader of subsequent slots.

Inflation in Solana is defined annually but applied at the epoch level. The inflation mechanics involve three key components: the predefined inflation schedule, adjustments based on slot duration, and the reward distribution logic. These are implemented within the Bank struct (runtime/src/bank.rs), which converts epochs to calendar years using the slot duration as a scaling factor.

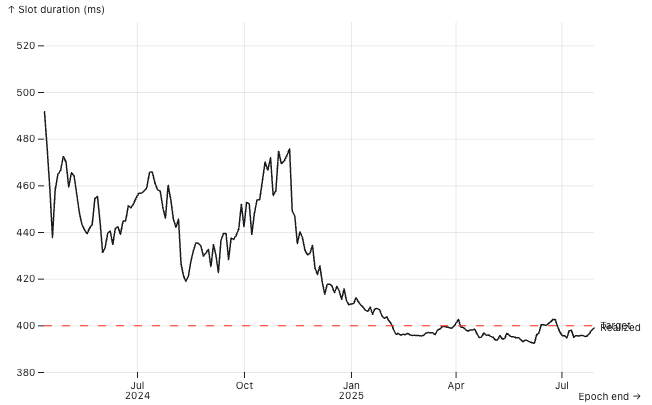

Slot duration is defined as ns_per_slot: u128 in Bank, derived from the GenesisConfig, with a default value of DEFAULT_NS_PER_SLOT = 400_000_000 (i.e., 400ms). Any deviation from this nominal value impacts real-world inflation dynamics.

The protocol computes the inflation delta per epoch using the nominal slot duration to derive the expected number of epochs per year (approximately 182.5), and thus the epoch fraction of a year (~0.00548). This delta is fixed and does not depend on the actual slot production speed. As a result, the effective annual inflation rate scales with the realized slot time: faster slots lead to more epochs per calendar year (higher total minting), while slower slots result in fewer epochs and thus reduced minting. For example:

As shown in the corresponding plot, real slot times fluctuate around the 400ms target. However, if a sufficient share of stake adopts timing games, average slot time may systematically exceed the nominal value, thereby suppressing overall staking yields. This effect introduces a distortion in the economic design of the protocol: slower-than-target slot times reduce total inflationary rewards without explicit governance changes. While the additional revenue from MEV and fees may partially offset this decline, it typically does not compensate for the loss in staking yield.

Moreover, this creates a strategic window: node operators controlling enough stake to influence network slot timing can engage in timing games selectively—prolonging slot time just enough to capture extra fees and MEV, while keeping the average slot time close to the 400ms target to avoid noticeable inflation loss. This subtle manipulation allows them to extract value without appearing to disrupt the protocol’s economic equilibrium.

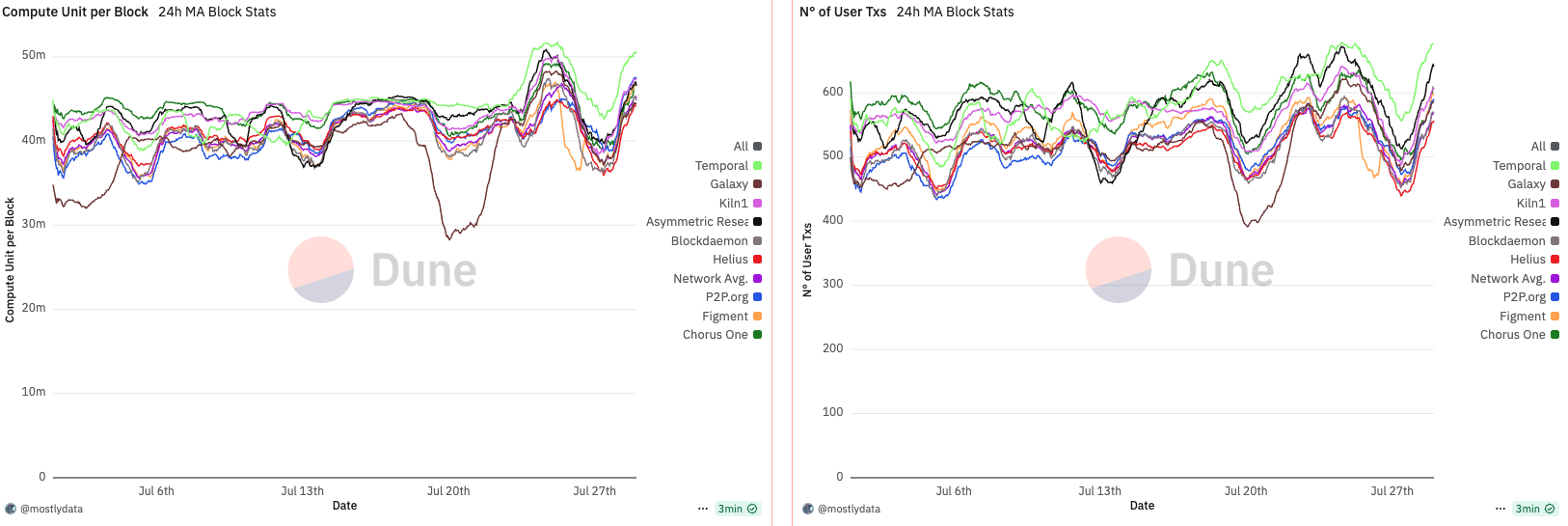

TPS is often cited as a key performance metric for blockchains, but its interpretation is not always straightforward. It may seem intuitive that delaying slot time would reduce TPS—since fewer slots per unit time implies fewer opportunities to process transactions. However, this assumption overlooks a critical factor: longer slot durations allow more user transactions and compute units (CUs) to accumulate per block, potentially offsetting the reduction in block frequency.

Empirical evidence from our experiment supports this nuance. During the period of artificially delayed slots (~480ms), we observed a ~100 transaction increase per block compared to other validators running the standard Agave codebase (we will address Firedancer in the next section). Specifically, our configuration averaged 550 transactions per block at 480ms slot time, while the rest of the network, operating at an average 396ms, processed ~450 transactions per block.

This results in:

Thus, despite reducing block frequency, the higher transaction volume per block actually resulted in a net increase in TPS. This illustrates a subtle but important point: TPS is not solely a function of slot time, but of how transaction throughput scales with that time.

CU per block is a more nuanced metric, requiring a broader temporal lens to properly assess the combined effects of block time and network utilization.

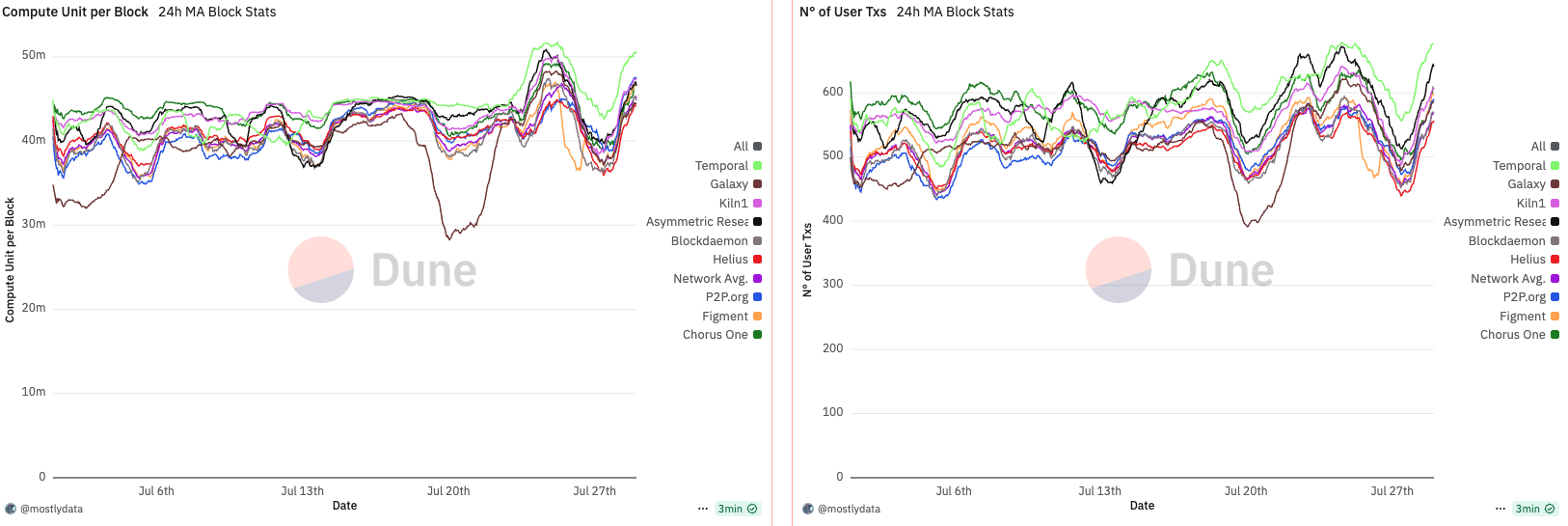

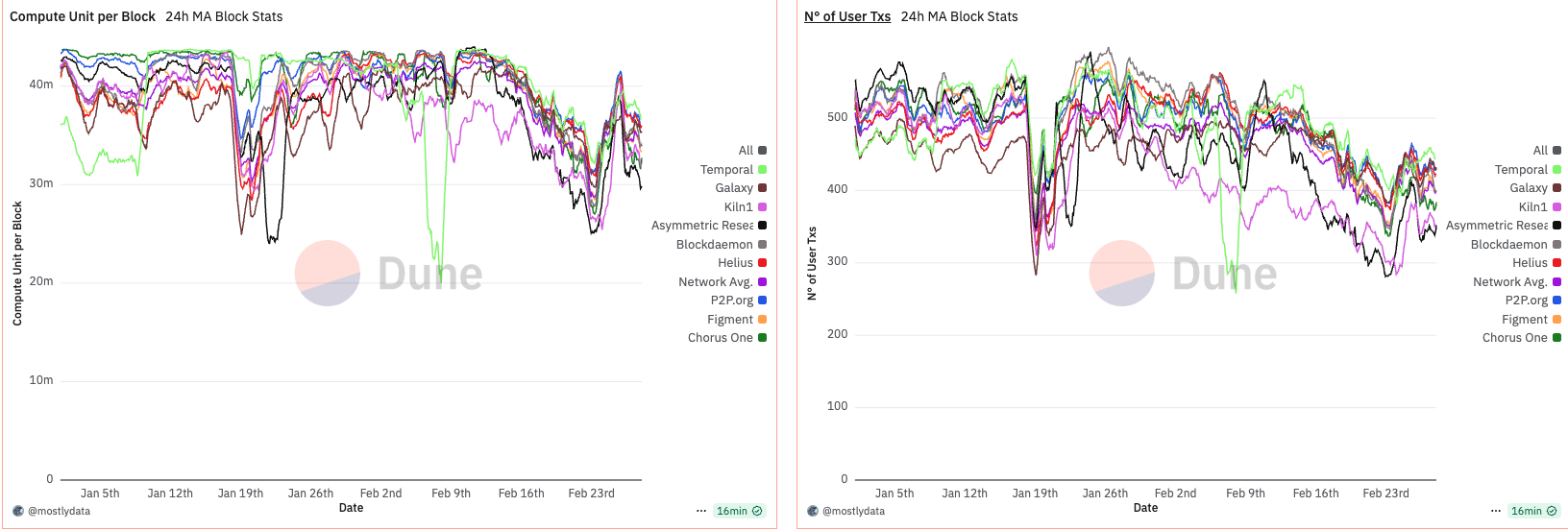

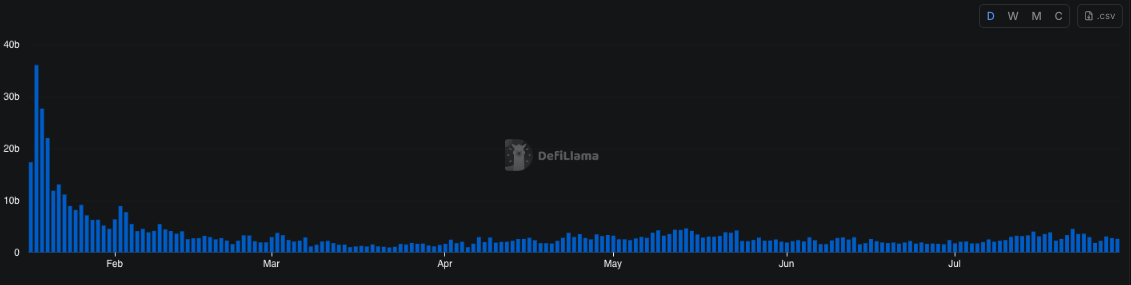

The first period of interest is January to February 2025, a phase marked by unusually high network activity driven by the meme coin season and the launch of various tokens linked to the Trump family. Notably, despite elevated traffic, we observe a dip in CU per block around January 19th, coinciding with the launch of the TRUMP token. This paradox—reduced CU per block during high demand—suggests an emerging inefficiency in block utilization.

At the time, the network-wide 24-hour moving average of CU per block remained significantly below the 48 million CU limit, with only rare exceptions. This indicates that, despite apparent congestion, blocks were not saturating compute capacity.

A structural shift occurred around February 13th, when approximately 88% of the network had upgraded to Agave v2.1.11. Following this, we observe a sharp and persistent drop in CU per block, implying a systemic change in block construction or scheduling behaviour post-upgrade. While several factors could be contributing—including transaction packing strategies, timing variance, and runtime-level constraints—this pattern underscores that software versioning and slot management can directly shape CU efficiency, especially under sustained demand.

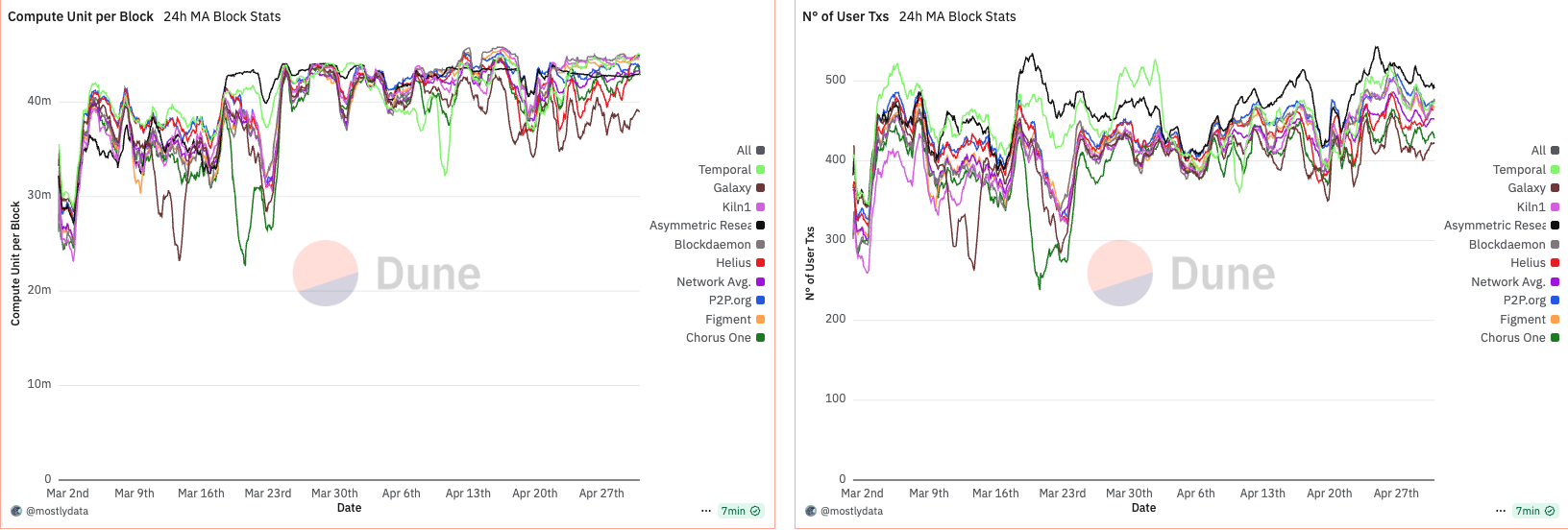

Anomalous behavior in CU per block emerges when analyzing the data from March to April 2025. During this period, CU usage per block remained unusually low—oscillating between 30M and 40M CU, well below the 48M limit. This persisted until around March 15th, when a sharp increase in CU per block was observed. Not coincidentally, this date marks the point at which over 66% of the stake had upgraded to Agave v2.1.14.

What makes this shift particularly interesting is its disconnect from network demand. A comparison with DeFi activity shows virtually no change between late February and early March. In fact, DeFi volumes declined toward the end of March, while CU per block moved in the opposite direction. This suggests that the rise in CU was not driven by increased user demand, but rather by validator behaviour or runtime-level changes introduced in the upgrade.

Throughout this period, the number of user transactions remained relatively stable. Notably, Firedancer (FD)—benchmarked via Asymmetric Research as a top-performing validator—began to include more transactions per block. FD also exhibited greater stability in CU usage, implying a more consistent packing and scheduling behaviour compared to Agave-based validators.

These observations suggest that CU per block is not merely a reflection of demand, but is heavily influenced by validator software, packing logic, and runtime decisions. The sharp rise in CU post-upgrade, despite declining network activity, points to a protocol-level shift in block construction rather than any endogenous change in user behaviour.

Notably, around April 14th, we observe a widening in the spread of CU per block across validators. This timing aligns with the effective increase in the maximum CU limit from 48M to 50M, suggesting that validators responded differently to the expanded capacity. Interestingly, FD maintained a remarkably stable CU usage throughout this period, indicating consistency in block construction regardless of the network-wide shift.

What emerges during this phase is a growing divergence between early adopters of timing games and fast, low-latency validators (e.g., Chorus One and Helius). While the former began pushing closer to the new CU ceiling, leveraging additional time per slot to pack more transactions, the latter maintained tighter timing schedules, prioritizing speed and stability over maximal CU saturation.

The picture outlined so far suggests a wider client-side inefficiency, where performance-first optimization—particularly among Agave-based validators—results in suboptimal block packaging. This is clearly highlighted by Firedancer (FD) validators, which, despite not engaging in timing games, consistently approached block CU saturation, outperforming vanilla Agave nodes in terms of block utilization efficiency.

This divergence persisted until some Agave validators began exploiting the inefficiency directly, leveraging the fact that extreme hardware-level optimization degraded packing efficiency under default conditions. By July, when we were fully operating with intentional slot delays, we observed that slot-time delayers were consistently packing blocks more effectively than fast, timing-agnostic validators.

Yet, during the same period, FD validators reached comparable levels of CU saturation—without modifying slot time—simply through better execution. This reinforces the view that the observed discrepancy is not a protocol limitation, but rather a shortcoming in the current Agave implementation. In our view, this represents a critical inefficiency that should be addressed at the client level, as it introduces misaligned incentives and encourages timing manipulation as a workaround for otherwise solvable engineering gaps.

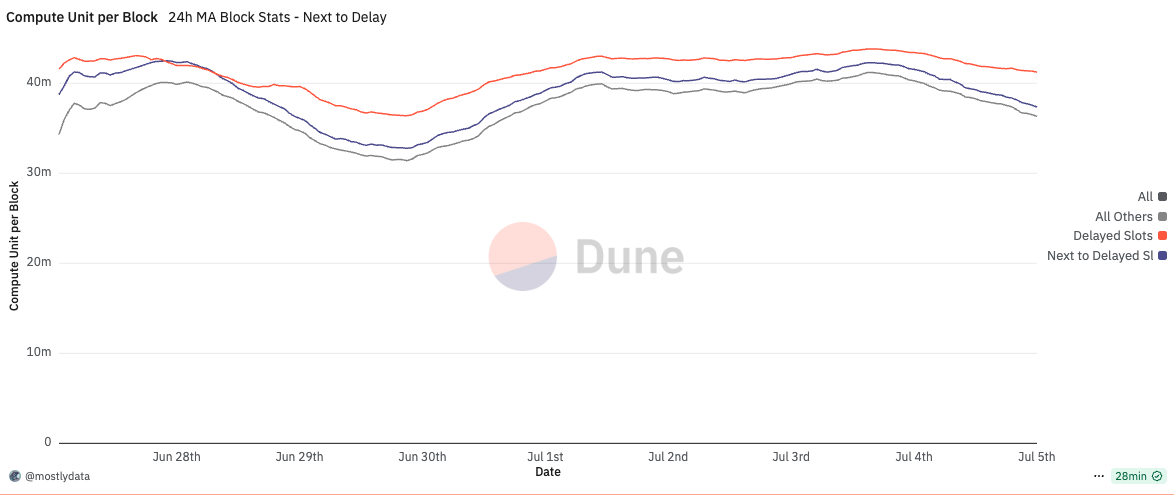

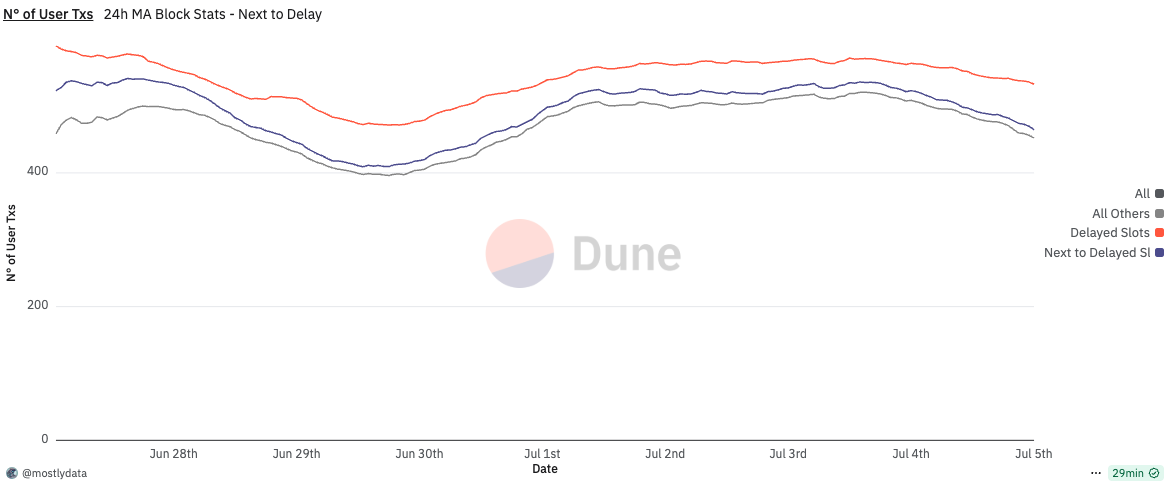

This brings us to the final piece of the puzzle. On Ethereum, prior research has shown that delaying slot time can enable the validator of slot N to “steal” transactions that would otherwise have been processed by the validator of slot N+1. On Solana, however, the dynamics appear fundamentally different.

While it is difficult to prove with absolute certainty that slot delayers are not aggregating transactions intended for subsequent slots, there are strong indications that this is not the mechanism at play. In our experiment, we only altered Proof of History (PoH) ticking, effectively giving the Agave scheduler more time to operate, without modifying the logic of transaction selection.

Agave’s scheduler is designed to continuously process transactions based on priority, and this core behaviour was never changed. Importantly, Firedancer's performance—achieving similar block utilization without delaying slot time—strongly suggests that the observed improvements from timing games stem from enhanced packaging efficiency, not frontrunning or cross-slot transaction capture.

Furthermore, when we examine the number of user transactions and CU per block for slots immediately following those subject to timing games, we observe that subsequent leaders also benefit from the delayed PoH, even when running an unmodified, vanilla Agave client, cfr. here. Compared to the network-wide baseline, these leaders tend to produce blocks with higher transaction counts and CU utilization, suggesting that the slower PoH cadence indirectly improves scheduler efficiency for the next slot as well. In other words, the gains from timing games can partially spill over to the next leader, creating second-order effects even among non-participating validators.

In this light, the extended time appears to function purely as a buffer for suboptimal packing logic in the Agave client, not as a window to re-order or steal transactions. This further supports the argument that what we’re observing is not a protocol-level vulnerability, but rather an implementation-level inefficiency that can and should be addressed.

This document has provided a quantitative and qualitative analysis of timing games on Solana, focusing on four critical dimensions: inflation rewards, transactions per second (TPS), compute unit (CU) utilization, and costs imposed on the next leader.

We began by quantifying the incentives: timing games are not just viable—they’re profitable. Our tests show that:

In the case of inflation, we showed that slot-time manipulation alters the effective mint rate: longer slots reduce inflation by decreasing epoch frequency, while shorter slots accelerate issuance. These effects accumulate over time and deviate from the intended reward schedule, impacting protocol-level economic assumptions.

For TPS, we countered the intuition that longer slots necessarily reduce throughput. In fact, because longer slots allow for higher transaction counts per block, we observed a slight increase in TPS, driven by better slot-level utilization.

The most revealing insights came from analyzing CU per block. Despite similar user demand across clients, Firedancer consistently saturated CU limits without altering slot timing. In contrast, Agave validators required delayed slots to match that efficiency. This points not to a network-level bottleneck but to a client-side inefficiency in Agave’s transaction scheduler or packing logic.

Finally, we investigated concerns around slot-boundary violations. On Ethereum, delayed blocks can allow validators to “steal” transactions from the next slot. On Solana, we found no strong evidence of this. The PoH delay only extends the scheduling window, and Agave’s priority-based scheduler remains unmodified. Firedancer’s comparable performance under standard timing supports the conclusion that the extra slot time is used purely for local block optimization, not frontrunning.

Altogether, the evidence suggests that timing games are compensating for implementation weaknesses, not exploiting protocol-level vulnerabilities. While we do not assert the presence of a critical bug, the consistent underperformance of Agave under normal conditions—and the performance parity achieved through slot-time manipulation—raises valid concerns. Before ending the analysis, it is worth mentioning that the idea of a bug, with more context around it, has been provided by the Firedancer team as well here.