At Solana Accelerate in May, Anza introduced Alpenglow, a new consensus mechanism capable of finalizing blocks in as little as 150ms. Overhauling consensus is a colossal task for any blockchain, but it’s just one of the major changes coming to Solana in the months ahead.

This week, Jito, a core piece in Solana’s infrastructure, announced the Block Assembly Marketplace (BAM). Together, Alpenglow and BAM completely rethink how Solana works. The new architecture will enable use cases previously out of reach, introduce new economic dynamics, reduce toxic MEV, and lay the groundwork for broader institutional adoption.

In this article, we’ll explore what’s changing, what it means for the network, validators, and users, and the challenges ahead.

At the heart of Solana’s upcoming infrastructure overhaul is the Block Assembly Marketplace (BAM). It introduces several changes:

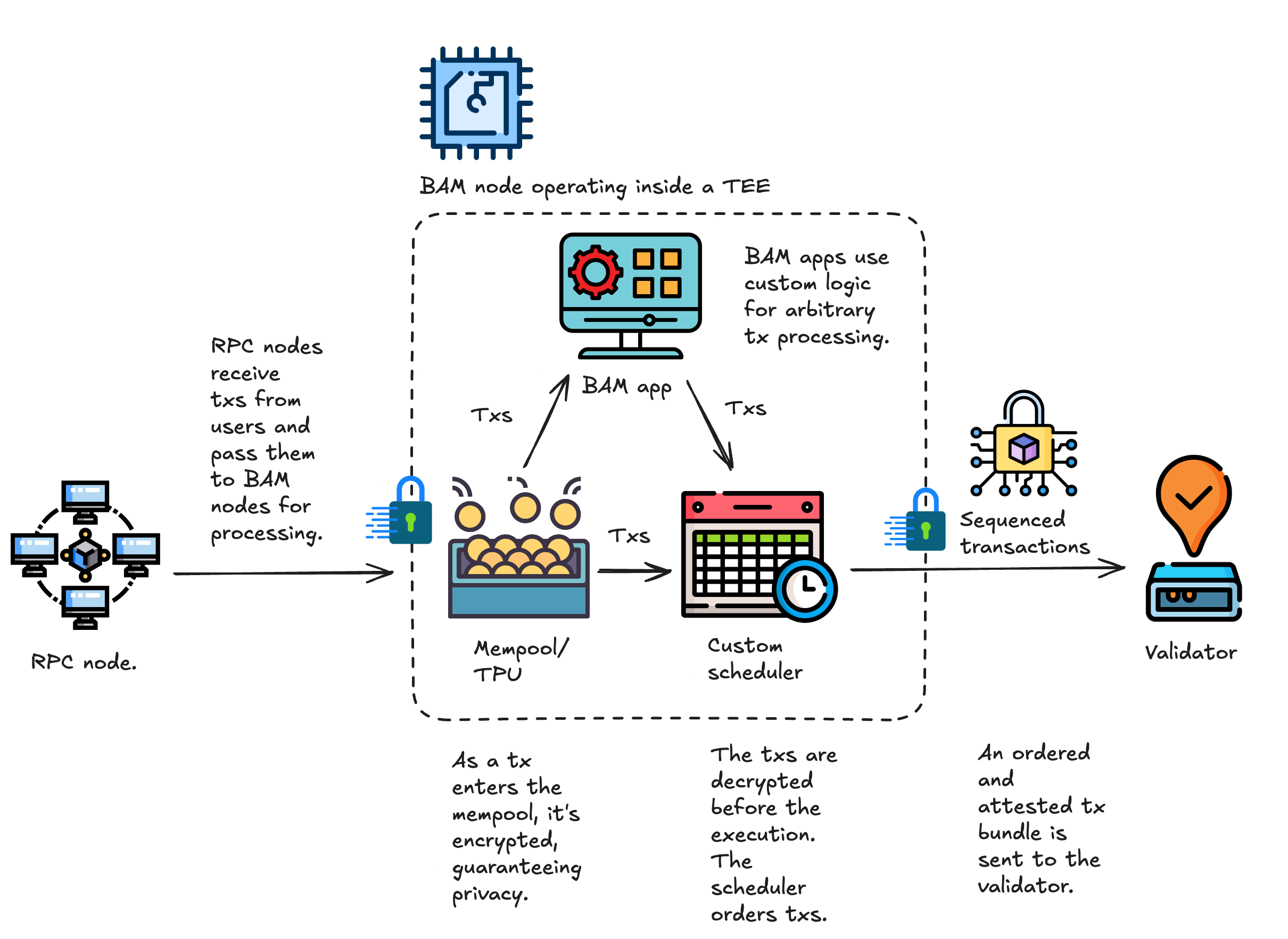

Here’s what the new transaction flow looks like:

A lot is happening here, so let’s break it down step by step.

Solana's new architecture is inspired by Flashbots' BuilderNet, where Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) play a central role. TEEs are isolated areas within processors (like Intel SGX or Intel TDX) that protect data and code execution from all external access.

In Solana’s upcoming design, TEEs enable:

The use of TEEs also comes with trade-offs. Their security has been questioned, and there’s even a dedicated site, sgx.fail, that tracks known vulnerabilities in Intel’s SGX platform. Common attack vectors include side-channel attacks (e.g., Spectre) or hardware-level vulnerabilities (e.g., Plundervolt). However, if such an attack is launched against Solana, the most severe likely consequence might be transaction reordering, including sandwiches, an arguably acceptable cost for revealing a vulnerability.

In the current Jito architecture, RPC nodes and validators send transactions to a relayer, the current leader (i.e., the validator building the block), and a few upcoming leaders. The relayer filters these transactions and passes them to the block engine. Meanwhile, MEV searchers create transaction bundles and also submit them to the block engine. The block engine then processes and forwards these transactions and bundles to the validators for inclusion in the block.

The new architecture changes this. BAM nodes take over the roles of both the block engine and the relayer. These specialized nodes receive transactions from RPCs, sequence them, and forward to validators. This effectively introduces Proposer-Builder Separation (PBS) to Solana.

Another feature of BAM nodes is support for customizable schedulers, which allow developers to influence the block-building process through Plugin apps.

Initially, Jito will operate all BAM nodes. Over time, the plan is to expand to a permissioned set of operators, with the long-term goal of supporting a permissionless model.

One of the most exciting innovations in the new Jito architecture is the introduction of Plugins, or interfaces that interact with BAM nodes. These plugins can access live transaction streams and use custom logic to influence ordering or insert their own transactions. While the scheduler still determines final ordering, plugins can use priority fees to shape block composition.

This opens up new possibilities for both developers and users. It also aligns with Solana’s IBRL philosophy, enabling new use cases that push the limits of what Solana currently supports.

From an economic standpoint, plugins introduce a revenue-sharing model that can benefit validators, delegators, and developers. That said, open questions remain about how different plugins will interact with each other, and how their economics will evolve.

Because plugins run within TEEs, they have full access to incoming transactions. This means the Plugins’ permissionlessness must be significantly constrained; otherwise, it would risk enabling harmful MEV extraction.

A practical example of plugin potential is how they might improve Central Limit Order Book (CLOB) exchanges on Solana.

CLOB exchanges let users place limit orders, specifying price, size, and direction. But building efficient, on-chain CLOBs on Solana is notoriously difficult due to:

Bulk Trade offers a new approach: directly integrating the order book into the validator stack. Orders are received through a dedicated port, matched deterministically in 25ms cycles across validators, and aggregated into a net-delta commitment that’s later posted onchain.

The downside? Validators must run additional software, which is a tough sell.

However, with BAM, this ultra-fast order-matching functionality could be implemented as Pugin. That makes adoption far easier without requiring validators to manage separate systems.

Plugins effectively extend Solana’s native capabilities. In this way, their role is comparable to that of L2s on Ethereum. However, because Plugins are built at the heart of Solana’s transaction pipeline, they contribute economic value to the network, rather than extracting it like traditional L2s often do.

That said, the approach isn’t without challenges, particularly for Plugins that must maintain shared state. Bulk Trade is a good example: its orders, cancellations, and fills need to be managed deterministically and synchronized across multiple nodes. The challenge is essentially a distributed consensus problem, but for high-frequency trading with sub-second finality. In such cases, the advancements in Alpenglow’s shred distribution system, Rotor, would hopefully provide meaningful support.

Ultimately, plugins bring three major benefits to Solana:

In the current Solana architecture, validators handle both transaction sequencing and execution. The new model separates these responsibilities: transaction sequencing is delegated to BAM nodes, while validators are responsible for executing and validating the proposed blocks.

Here’s how it works:

To support this model, BAM validators will run an updated version of the Jito-Solana client, which will be adapted to receive transactions from BAM nodes. In the future, BAM will integrate as a modular scheduler within Agave and Firedancer, allowing validators to leverage the optimized scheduling of BAM and the improved performance of these clients.

The changes introduced by the new architecture fall into three categories:

It’s too early to say which will have the most significant impact, but each will substantially contribute to changing Solana’s economics and dynamics. Let’s start with PBS.

So far, Ethereum is the only blockchain that has implemented PBS. Traditionally, validators build (select and order transactions) and propose (submit the block to the network). PBS splits these roles, introducing specialized builders alongside proposers.

The motivation is straightforward: specialized builders can construct more valuable blocks and extract MEV more efficiently. PBS helps address the fact that most validators lack the resources or sophistication to maximize block value on their own.

PBS is implemented on Ethereum offchain via a sidecar software called MEV-Boost. Here’s how it works:

This model improves block quality but comes with trade-offs, especially around centralization.

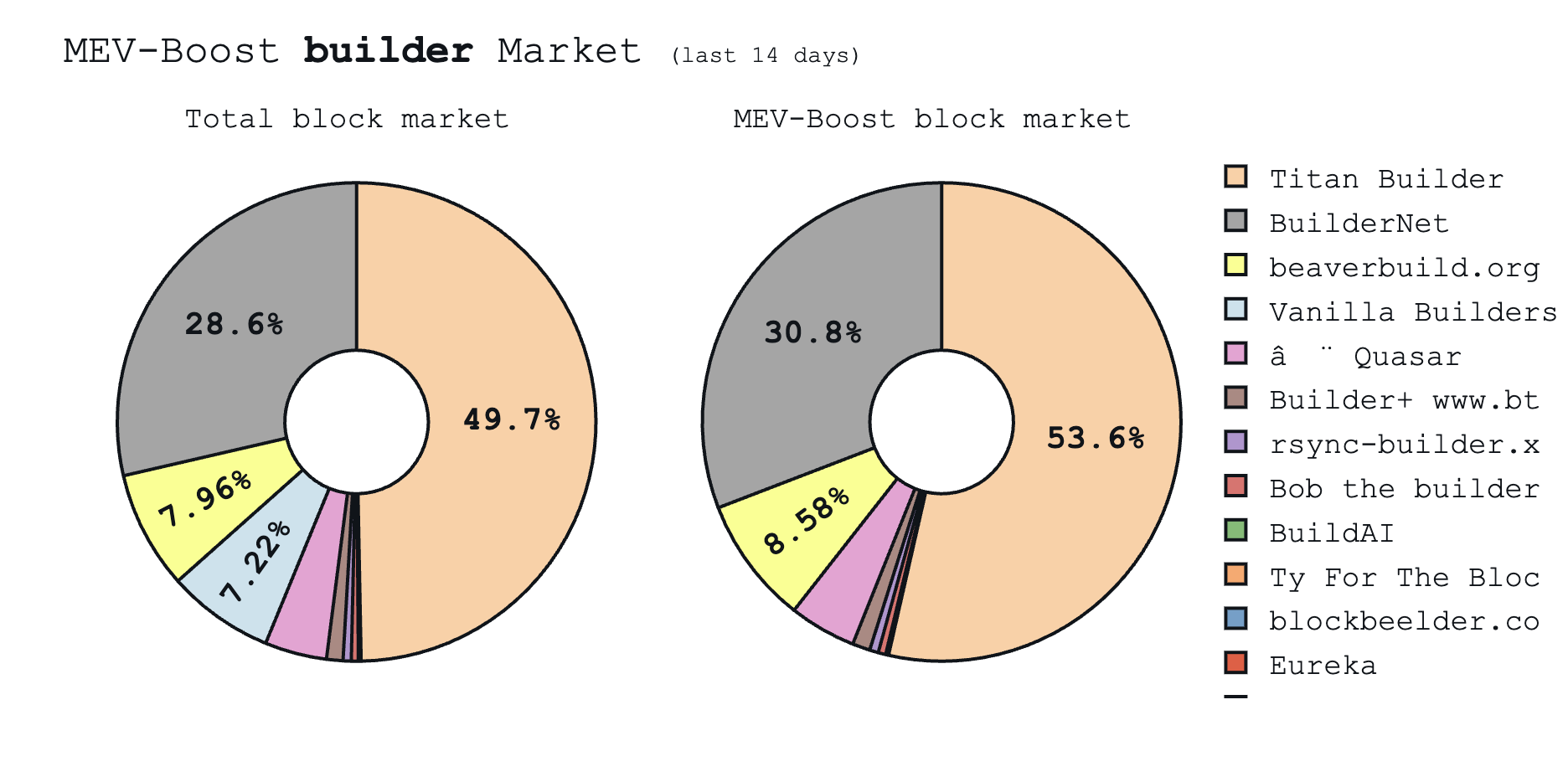

Currently, two builders, Titan and Beaverbuild, create over 65% of blocks on Ethereum (down from over 80%). This makes block building the centralization hotspot in Ethereum’s transaction pipeline.

Much of this concentration comes from private transaction orderflow. Builders enter exclusive deals with wallets and exchanges to receive transactions before they hit the public mempool, which creates strong feedback loops that reinforce their dominance.

In late 2024, Flashbots introduced BuilderNet to tackle these centralization risks. BuilderNet, the main inspiration for the BAM architecture, allows multiple parties to operate a shared builder, offering equal access to orderflow at the network level. MEV proceeds are then distributed to orderflow providers based on open-source refund logic.

Participation is permissionless for both builders and orderflow providers. The broader goal is to prevent any single party from dominating block building.

Today, BuilderNet is jointly operated by Flashbots, Beaverbuild, and Nethermind and plans to expand. Within eight months, BuilderNet captured 30% of the market. Beaverbuild has largely transitioned its infrastructure over, and plans a full migration.

While promising, BuilderNet's long-term effectiveness remains uncertain. As long as individual builders can offer better orderflow deals to wallets, market makers, searchers or exchanges, centralization incentives will not disappear.

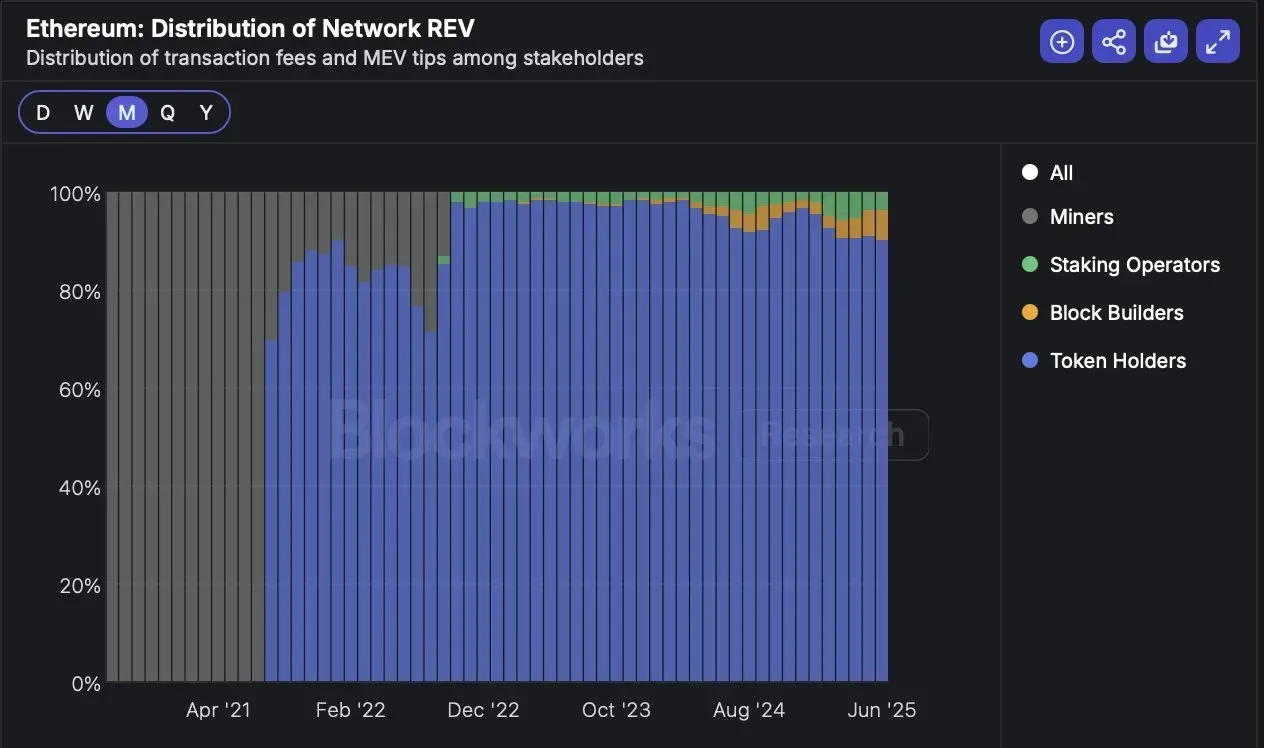

PBS in Solana will introduce several economic shifts, but also some trade-offs, especially for validators:

Decreased MEV share for validators and delegators: With a new player in the block-building pipeline, rewards must be split. As seen on Ethereum, this can reduce delegator rewards and validator income.

Elimination of client-level optimizations

While these are important points, the upside for the broader ecosystem is real: PBS improves network efficiency and user experience by enabling more competitive, higher-value block construction.

PBS seems inevitable as networks reach sufficient activity and ecosystem maturity. The incentives to fix block building inefficiency become strong enough that a market participant will always rise to fix it. PBS reflects this evolution: a step toward optimized infrastructure that benefits the network and its users. We should all be happy that Solan has reached this point.

Beyond economics, one of BAM's key goals is reducing toxic MEV. Solana’s new design includes two security mechanisms to help achieve this:

These safeguards raise the bar for MEV attacks significantly. That said, risks remain:

While MEV will always be a game of cat and mouse, BAM makes harmful extraction meaningfully harder. While this benefits all users, it is especially important for attracting institutions that demand deterministic execution, privacy, and auditability. By enabling these features, BAM can drive higher activity and volume on Solana, ultimately increasing total network REV.

Solana will likely face some of the same hurdles Ethereum encountered in its PBS transition:

Solana is entering a new phase, defined not just by faster Alpenglow consensus, but by a fundamental rethinking of how blocks are built, ordered, and validated.

With the introduction of BAM, Solana is embracing Proposer-Builder Separation, TEE-based privacy protections, and programmable transaction pipelines through Plugins. These structural upgrades shift how value is created and flows through the network.

Yes, there are trade-offs. Validators may lose some of the flexibility and MEV opportunities they enjoy today. Client-level optimizations will become less relevant. Decentralization risks around block building will also be an issue. But these changes come with big upsides:

The transition won’t be easy. TEEs must be widely adopted, and builders and validators must adjust to new roles.

At Chorus One, we support upgrades that make Solana more efficient, resilient, and user-friendly. BAM brings these benefits. We’re excited to help build and support the next phase of Solana’s growth!

Solana remains one of the fastest and most adopted blockchains in the crypto ecosystem. In this context, we view Alpenglow as a bold and necessary evolution in the design of Solana’s consensus architecture.

Our position is fundamentally in favour of this shift. We believe that Alpenglow introduces structural changes that are essential for unlocking Solana’s long-term potential. However, with such a radical departure from the current Proof-of-History (PoH) based system, a careful and transparent analysis of its implications is required.

This document is intended as a complement to existing reviews. Rather than offering summary of the Alpenglow consensus, well covered in resources like the Helius article, our aim is to provide a rigorous peer review and a focused analysis of its economic incentives and potential trade-offs. Our goal is to provide a critical perspective that informs both implementation decisions and future protocol research.

The article is structured as follows. In Sec. 2 we go straight into the Alpenglow whitepaper to provide a peer review. Precisely, in Sec. 2.1 we analyze the less than 20% Byzantine stake assumption. In Sec. 2.2 we explore the effects of epochs on rewards compounding. In Sec. 2.3 we assess the implication of reduced slot time on MEV. In both Sec. 2.4 and 2.5 we study some implications of propagation design as presented in the original paper. In Sec. 2.6 we explore the possibility to perform Authenticated DDoS attack on the network. In Sec. 2.7 we assess some network assumptions and systemic limitations. Finally, in Sec. 2.8 we discuss some implications of PoH removal.

In Sec. 3 we explore some implications that arise from how tasks are rewarded under Alpenglow. Precisely, in Sec. 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3 we present three ways in which a sophisticated node operator can game the reward mechanisms. In Sec. 3.4 we assess the effects of randomness on rewards.

In this section, we take a critical look at the Alpenglow consensus protocol, focusing on design assumptions, technical trade-offs, and open questions that arise from its current formulation. Our intent is to highlight specific areas where the protocol’s behaviour, performance, or incentives deserve further scrutiny.

Where relevant, we provide probabilistic estimates, suggest potential failure modes, and point out edge cases that may have meaningful consequences in practice. The goal is not to undermine the protocol, but to contribute to a deeper understanding of its robustness and economic viability.

Alpenglow shifts from a 33% Byzantine tolerance to a 20% in order to allow for fast (1 round) finalization. While the 5f+1 fault tolerance bound theoretically allows the system to remain safe and live with up to 20% Byzantine stake, the assumption that Byzantine behaviour always takes the form of coordinated, malicious attacks is often too narrow. In practice, especially in performance-driven ecosystems like Solana, the boundary between rational misbehaviour and Byzantine faults becomes blurred.

Validators on Solana compete intensely for performance, often at the expense of consensus stability. A prominent example is the use of mod backfilling. While not explicitly malicious, such practices deviate from the intended protocol behaviour and can introduce systemic risk.

This raises a key concern: a nontrivial fraction of stake, potentially exceeding 20%, can engage in behaviours that, from the protocol’s perspective, are indistinguishable from Byzantine faults. When performance optimization leads to instability, the classical fault threshold no longer guarantees safety or liveness in practice.

Alpenglow models this possibility by allowing an additional 20% of the stake to be offline. This raises the resistance to 40% of the stake, being more aligned with a real implementation of a dynamical and competitive distributed system.

An essential question arising from the 5f+1 fault-tolerance threshold in Alpenglow is whether the current inflation schedule adequately compensates for security. To address this, we use the same formalism developed in our SIMD-228 analysis.

The primary task is to determine under what conditions the overpayment statement holds for a 20% Byzantine + 20% crashed threshold. To assess if the current curve is prone to overpayment of security, we need to study the evolution of the parameters involved. This is not an easy task, and each model is prone to interpretation.

The model is meant to be a toy-model showing how the current curve can guarantee the security of the chain, overpaying for security based on different growth assumptions. The main idea is to assess security as the condition

where the profit is estimated assuming an attacker can drain the whole TVL. Precisely, since the cost to control the network is >60% of total stake S (Alpenglow is 20% Byzantine + 20% crash-resistant), we have that the cost to attack is 0.6 × S, and the profit is the TVL. In this way, the chain can be considered secure provided that

In our model, we consider the stake rate decreasing by 0.05 following the equivalent of Solana PoH 150 epochs, based on the observation done in the SIMD-228 analysis. We further consider a minimum stake rate of 0.33 (in order to compare with the SIMD-228 analysis), a slot time of 400ms, 18,000 slots per epoch, and we fix the TVL to be DeFi TVL. We also assume 0 SOL as burn rate since we will not have vote transactions anymore, and we don’t know how many transactions Solana will handle per slot under Alpenglow.

It is worth noting that, these parameters are based on empirical data and what is used as default in the Alpenglow withepaper (page 42, Table 9).

The first case we want to study is when TVL grows faster than SOL price. We assumed the following growth rates:

The dynamical evolution obtained as an outcome of these assumptions is depicted below.

With the assumed growth rate, the current inflation schedule is projected to maintain adequate security for slightly more than two years. Notably, this has no real difference when compared to the timeline derived from the same growth scenario applied to the current Solana PoH implementation.

It is worth reiterating that the toy model presented here is a simplified parametrization of reality. The goal is not to precisely determine whether the current inflation schedule leads to overpayment or underpayment for security. Rather, it serves to quantify the impact of lowering the takeover threshold from 66% to 60% of stake under Alpenglow.

This shift implies that an adversary must control a smaller fraction of the stake to compromise the system, thereby reducing the cost of an attack. As the model shows, even a 6 percentage point increase may appear substantial, but in a scenario with fast TVL growth, the system shows virtually no difference compared to the PoH consensus. This suggests that Alpenglow’s higher fault tolerance comes at a modest and bounded cost, at least under optimistic growth assumptions.

As in the PoH scenario, if we assume SOL’s price growth rate surpasses the growth rate of the network’s TVL, the current inflation schedule would lead to approximately ten years of overpayment for network security, cfr. SIMD-228: Market Based Emission Mechanism.

Alpenglow and the current Solana PoH implementation differ in the frequency of reward compounding. While both mechanisms eventually use a similar inflation curve, they distribute and compound rewards at vastly different rates: a lower number of slots per epoch increases the number of epochs per year in Alpenglow, compared to Solana PoH.

This difference in epoch definition (and slot time) has a direct impact on the effective APY received by validators. Even when the nominal inflation rate is identical, more frequent compounding leads to higher APY, due to the exponential nature of compound interest.

Formally, for a given nominal rate r and compounding frequency n, the APY is given by:

With Alpenglow’s much higher n, this yields a strictly larger APY than PoH under equivalent conditions. In the limit as n -> ∞, the APY converges to e^r-1, the continuously compounded rate. Alpenglow therefore approximates this limit more closely, offering a higher geometric growth of rewards.

This behaviour is illustrated in the figure above, which compares the compounded returns achieved under both mechanisms across different stake rates. The difference is particularly noticeable over short to medium time horizons, where the higher compounding frequency in Alpenglow yields a tangible compounding advantage. However, as the projection horizon extends, e.g., over 10 years, the difference becomes increasingly marginal. This is due to two effects: first, the declining inflation rate reduces the base amount subject to compounding; second, the PoH system's less frequent compounding becomes less disadvantageous once inflation levels off. In long-term projections, the frequency of compounding is a second-order effect compared to the shape of the inflation curve and the total staking participation.

A central design parameter in Alpenglow is the network delay bound Δ, which defines the maximum time within which shreds and votes are expected to propagate for the protocol to maintain liveness. In practice, Alpenglow reduces Δ to nearly half of Solana’s current grace period (~800 ms), aiming for faster finality and tighter synchronization.

It is worth mentioning that, Alpenglow will not directly lower the slot time, which will be kept fixed at 400ms. However, Alpenglow makes lower slot time more reliable, meaning that in the future slot time can be lowered.

In this section, we consider the impacts of reducing network delay on arbitrage opportunities. We know, from Milionis et al, that the probability of finding an arbitrage opportunity between 2 venues is given by

where λ is the Poisson rate of block generation (i.e. the inverse of mean block time, Δt = λ⁻¹, γ is the trading fee, and σ is the volatility of the market price’s geometric Brownian motion.

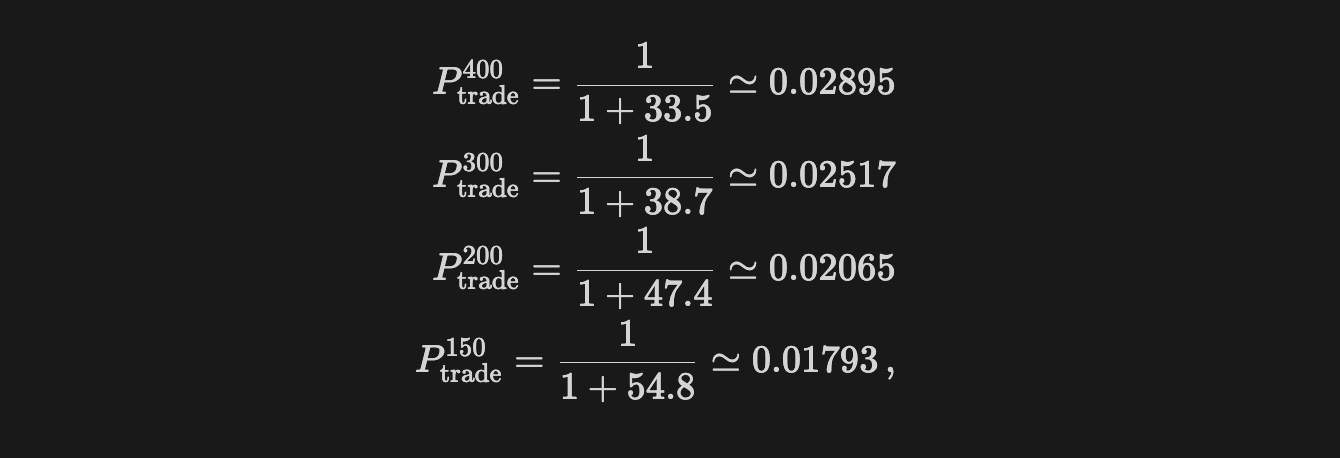

From the trade probability, it is clear that reducing block time from 400ms also reduces the probability of finding an arbitrage opportunity within a block. Precisely, if we assume a daily volatility of 5% (σₛₑcₒₙd ~ 0.02%) and a fee γ = 0.3% we get

which represents a ~38% reduction on the probability we find a profitable arb.

The reduction on arbitrage probability clearly affects final rewards. Precisely, Corollary 2 of Milionis et al provides a closed form for arbitrage profit normalized by pool value V(p) in the case of a CPMM,

Indeed, by taking the ratio between the arbitrage profits in the case of different block times, we get

This means that the revenue from the same arbitrage opportunity decreased by ~38.2%. The same result still holds if the DEX implements concentrated liquidity, we have a similar result that can be obtained using Theorem 3 of Milionis et al (Asymptotic Analysis), which leads to

where y*(p) = –L / (2√p) within the price range [pa, pb].

It is worth noting that the functional form is a consequence of the fact that liquidity is concentrated within a price range. If the market price or pool price exists in this range, arbitrage profits are capped, as trades can only adjust to p_a or p_b. This reduces the magnitude of arbitrage profits compared to CPMMs for large mispricing.

It follows that the arb difference is dependent just from Ptrade, that is

which is consistent with the CPMM result.

A direct consequence of reducing the “grace period” to approximately 400 ms, combined with the associated effects on arbitrage profitability, is the emergence of timing games. Sophisticated node operators are incentivized to engage in latency-sensitive strategies that exploit their physical proximity to the cluster. In particular, by positioning infrastructure geographically close to the majority of validators, they can receive transactions earlier, selectively delay block propagation, and increase their exposure to profitable MEV opportunities.

This behaviour may lead to a feedback loop: as Δ shrinks, the value of low-latency positioning increases, pushing operators to concentrate geographically, thereby undermining the network’s decentralization. While such latency-driven optimization already occurs under PoH, Alpenglow’s smaller Δ significantly amplifies its economic and architectural consequences.

To assess the impact of block time on sandwich attack profitability in a blockchain, we derive the probability p(tau) of successfully executing a sandwich attack, where tau is the slot time (time between blocks).

A sandwich attack involves an attacker detecting a victim’s transaction that impacts an asset’s price, submitting a front-run transaction to buy before the victim’s trade, and a back-run transaction to sell afterward, exploiting the price movement.

Transactions arrive at the mempool as a Poisson process with a blockchain transaction rate of Λ = 1,000 TPS, yielding a per-block rate λ = Λ·τ. Blocks are produced every τ seconds. The victim’s transaction is one of these arrivals, and we consider its arrival time tᵥ within the interval [0, τ]. Conditional on at least one transaction occurring in [0, τ], the arrival time of the first transaction is uniformly distributed over [0, τ]. Indeed, the Poisson process’s arrival times, conditioned on N(τ) = k ≥ 1, result in k arrival times T₁, T₂, …, Tₖ, which are distributed as independent uniform random variables on [0, τ]. If the victim’s transaction is any one of these arrivals, chosen uniformly at random, its arrival time tᵥ is equivalent to a single uniform random variable on [0, τ], so tᵥ ~ Uniform[0, τ].

The attacker detects the victim’s transaction and prepares the attack with latency d, submitting front-run and back-run transactions at time tᵥ + d, where tᵥ is the victim’s arrival time. We focus on the single-block sandwich, where all transactions are included in the same block in the correct order, ensured by high priority fees or Jito tips.

For a successful single-block sandwich, the attacker must submit the front-run and back-run transactions at tᵥ + d, and all three transactions (front-run, victim, back-run) must be included in the block at τ. The submission condition is tᵥ + d ≤ τ.

Since tᵥ ~ Uniform[0, τ], the probability density function is f(tᵥ) = 1 / τ, and the probability of submitting in time is

If τ < d, then tᵥ + d > τ for all tᵥ ∈ [0, τ], making submission impossible, so P(tᵥ ≤ τ − d) = 0. The back-run is submitted at tᵥ + d + δ, where δ is the preparation time for the back-run. Assuming δ ≈ 0 (realistic for optimized MEV bots), both transactions are submitted at tᵥ + d, and the same condition applies. We assume the block has sufficient capacity to include all three transactions, and the attacker’s fees/tips ensure the correct ordering (front-run, victim, back-run) with probability 1. Thus, the probability of a successful sandwich is:

This linear form arises because the uniform distribution of tᵥ implies that the fraction of the slot interval where tᵥ ≤ τ − d scales linearly with τ − d. The profitability of a sandwich attack can be written as

where ε is the slippage set from the victim’s transaction, V is the victim’s volume, and F is the fee. To quantify the relative change when reducing block time from τ₄₀₀ = 0.4 s to τ₁₅₀ = 0.15 s, we can compute

since the profit per executed sandwich is independent of block time. If we assume d = 50 ms, we get

indicating that the profit with a slot time of 400 ms is 31.25% higher than the profit with a slot time of 150 ms (or equivalently, we have a 23.8% reduction in sandwich profits with Alpenglow).

Before ending the section, it is worth mentioning that, in real cases, sandwich attacks suffer from interference (e.g., from competitors). Precisely, on Solana, transactions are processed in a loop during the slot time. This means that, if the loop lasts for tₗₒₒₚ, there is a temporal window [tᵥ, tᵥ + tₗₒₒₚ] where interfering transactions can arrive. Since these transactions still arrive following a Poisson process, we know that the probability of no interference (i.e., no interfering transaction arrives in tₗₒₒₚ) is

where Λᵢₙₜ is the TPS for interfering transactions. This factor translates into a probability of a successful sandwich of the form

This is a term that depends on the time needed to process transactions in a loop, which in principle is independent of the block time. In case this tₗₒₒₚ is reduced when reducing slot time, sandwich profitability will always increase by going from 400 ms to 150 ms.

Alpenglow specifies that once a relay receives its assigned shred, it broadcasts its shred to all nodes that still need it, i.e., all nodes except for the leader and itself, in decreasing stake order (cfr. Alpenglow paper page 13). While this design choice appears to optimize latency toward finality, it introduces important asymmetries in how information is disseminated across the network.

From a protocol efficiency standpoint, prioritizing high-stake validators makes sense: these nodes are more likely to be selected as voters, and their early participation accelerates the construction of a supermajority certificate. The faster their votes are collected, the sooner the block can be finalized.

However, this propagation order comes at the expense of smaller validators, which are placed at the tail end of the dissemination process. As a result:

In short, while stake-ordered propagation helps optimize time-to-finality, it imposes a latency tax on small validators, which may undermine long-term decentralization by suppressing their economic participation.

However, it is worth mentioning that, Turbine has more than one layer, meaning that most small stake may get the shreds with multiple network delays. In principle, with Rotor, this stake is only impacted by the transmission delay of the relay.

Lemma 7 presents a probabilistic bound ensuring that a slice can be reconstructed with high probability, provided a sufficient number of honest relays. While the lemma is mathematically sound, its real-world implications under the chosen parameters raise several concerns.

In particular, the paper adopts a Reed–Solomon configuration with Γ = 64 total shreds and a decoding threshold γ = 32, meaning that any 32 out of 64 shreds are sufficient to reconstruct a slice. Each shred is relayed by a node sampled by stake, and blocks are composed of 64 slices. Finality (via Rotor) requires all slices to be reconstructed, making the system sensitive to even a single slice failure.

The authors justify slice reliability using a Chernoff bound, but for Γ = 64, this is a weak approximation: the Chernoff bound is asymptotic and performs poorly in small-sample regimes. Using an exact binomial model instead, we can estimate failure probabilities more realistically.

Assume 40% of relays are malicious and drop their shreds (pₕₒₙₑₛₜ = 0.6). The probability that fewer than 32 honest shreds are received in a single slice is:

or

This gives P(X < 32) = 0.06714, which represents the single slice failure probability. Since Rotor requires all 64 slices to succeed, the block success probability becomes:

from which the block failure probability is

This is a very high failure probability in the case of a 40% Byzantine stake.

The situation improves only if:

For instance, with Γ = 265 and γ = 132, the slice failure rate under 40% Byzantine stake drops dramatically (though still around 3%), but this imposes higher network and computation costs.

The issue, then, is not the lemma itself, but the practicality of its parameters. While the theoretical bound holds as γ → ∞, in real systems with finite Γ, the choice of redundancy has significant implications:

Alpenglow’s messaging system relies on small (<1,500 byte) UDP datagrams for vote transmission (Section 1.4, Page 6). These messages are authenticated using QUIC-UDP or traditional UDP with pairwise message authentication codes (MACs), derived from validator public keys. On receipt, validators apply selective storage rules—only the first notarization vote per block from a given validator is stored (Definition 12, Page 17), with all duplicates ignored.

While this mechanism limits the impact of duplicate votes on consensus itself, it does not eliminate their resource cost. In practice, nodes must still verify every message’s MAC and signature before deciding to store or discard it. This opens a subtle but important attack vector: authenticated DDoS.

A validator controlling less than 20% of the stake can send large volumes of valid-looking, authenticated votes, either well-formed duplicates or intentionally malformed packets. These messages will be processed up to the point of verification, consuming CPU, memory, and network bandwidth on recipient nodes. If enough honest nodes are affected, they may be delayed in submitting their own votes.

This has two possible consequences:

1. Triggering Skip Certificates:

If more than 60% of stake skip votes, even if the leader and most voters were honest. While Alpenglow preserves safety in such cases, liveness is degraded.

2. Selective performance degradation:

Malicious actors could preferentially target smaller or geographically isolated validators, increasing their latency and further marginalizing them from the consensus process.

It’s important to stress that the attack cost is minimal: only the minimum stake required to activate a validator is needed. Indeed, in Alpenglow, votes are not transactions anymore, and SOL does not have the goal of being a spam protection token. Once active, a malicious node with valid keys is authorized to send signed votes, and these must be processed by peers. Unlike traditional DDoS, where filtering unauthenticated traffic is trivial, here the system's correctness depends on accepting and validating messages from all honest-looking peers.

While Alpenglow does not rely on message ordering or delivery guarantees, it remains vulnerable to resource exhaustion via authenticated spam, especially under adversaries who do not need to compromise safety thresholds to cause localized or network-wide disruption.

Several aspects of Alpenglow’s evaluation rest on assumptions about network behaviour and validator operations that, while simplifying analysis, may obscure practical challenges in deployment.

The simulations in the paper assume a constant network latency, omitting two critical factors that affect real-world performance:

These effects can meaningfully impact both block propagation and vote arrival times, and should be explicitly modelled in simulations.

Another element that requires a deep dive is the distinction between message reception and message processing. While validators may receive a shred or vote in time, processing it (e.g., decoding, MAC verification, inclusion in the vote pool) introduces a non-trivial delay, especially under high network load.

The absence of empirical measurements for this processing latency, especially under saturated or adversarial conditions, may limit the trustworthiness of the estimated time-to-finality guarantees.

Finally, Section 3.6 (Page 42) assumes that stake is a proxy for bandwidth, that is, validators with more stake are expected to provide proportionally more relay capacity. However, this assumption can be gamed. A single operator could split its stake across multiple physical nodes, gaining a larger share of relaying responsibilities without increasing aggregate bandwidth. This decouples stake from actual network contribution, and may allow adversarial stake holders to degrade performance or increase centralization pressure without being penalized.

One consequence of removing PoH from the consensus layer is the loss of a built-in mechanism for timestamping transactions. In Solana’s current architecture, PoH provides a cryptographic ordering that allows validators to infer the age of a transaction and deprioritize stale ones. This helps filter transactions likely to fail due to state changes (e.g., nonces, account balances) without incurring full execution cost.

Without PoH, validators must treat all transactions as potentially viable, even if many are clearly outdated or already invalid. This increases the computational burden during block execution, as more cycles are spent on transactions that ultimately revert.

Current on-chain data show that failed bot transactions account for ~40% of all compute units (CUs) used, but only ~7% of total fees paid. In other words, a disproportionate share of system capacity is already consumed by spammy or failing transactions, and removing PoH risks further exacerbating this imbalance by removing the only embedded mechanism for temporal filtering.

While PoH removal simplifies protocol architecture and decouples consensus from timekeeping, it may unintentionally degrade execution efficiency unless new mechanisms are introduced to compensate for the loss of chronological ordering.

The Alpenglow whitepaper doesn’t provide a full description of how rewards are partitioned among different tasks fulfilled by validators. However, there are features that are less dependent on actual implementation. With this in mind, this section is focussed on describing some properties may arise from the rewarding system.

As described in the paper, during an epoch e, each node counts how many messages (weighted messages, or even bytes) it has sent to every other node and received from every other node. So every node accumulates two vectors with n integer values each. The nodes then report these two vectors to the blockchain during the first half of the next epoch e + 1, and based on these reports, the rewards are being paid. This mechanism mostly applies to Rotor and Repair, since voting can be checked from the signatures in the certificate.

For Repair, while the design includes some cross-validation, since a validator vᵢ sends and receives repair shreds and reports data for other validators vⱼ ≠ vᵢ, there is still room for strategic behaviour. In particular, since packet loss is inherent to UDP-based communication, underreporting repair messages received from other validators cannot easily be flagged as dishonest. As a result, nodes are not properly incentivized to provide accurate reporting of messages received, creating a gap in accountability.

The situation is more pronounced for Rotor rewards, which are entirely based on self-reporting. When a validator vᵢ is selected as a relay, it is responsible for disseminating a shred to all validators (except itself and the leader). However, because there is no enforced acknowledgment mechanism, rewards cannot depend on whether these shreds are actually received by every node, only on whether the slice was successfully reconstructed. In this framework, a rational relay is incentivized to minimize dissemination costs by sending shreds only to a subset of high-stake validators, sufficient to ensure that γ shreds are available for decoding. This strategy reduces bandwidth and CPU usage while preserving the probability of slice success, effectively allowing relays to free-ride while still claiming full credit in their self-reports.

As discussed in Sec. 2.7.3, a node operator can reduce hardware costs by splitting the stake across multiple identities, exploiting the fact that expected bandwidth delivery obligations are proportional to stake. This allows the operator to distribute the load more flexibly while maintaining aggregate influence.

Alpenglow paper, in Sec. 3.6, introduces a mechanism that penalizes validators with poor performance. Precisely, the selection weight of these validators is gradually reduced, diminishing their likelihood of being chosen to do tasks in future epochs. While this mechanism intends to enforce accountability, it also creates a new incentive to underreport. Since selection probability affects expected rewards, validators now have a strategic reason to downplay the observed performance of peers.

In this context, underreporting becomes a rational deviation: by selectively deflating the recorded bandwidth contribution of others, a validator can increase the relative selection weight of its own stake. This dynamic may further erode the trust assumption behind self- and peer reporting, and eventually amplify the economic asymmetry between high- and low-resource participants.

Although Alpenglow removes explicit vote transactions, its reward mechanism still admits a form of time-variability compensation gameability. Specifically, there exists a potential vulnerability in which a validator can strategically delay its vote to maximize the likelihood of earning the special reward for broadcasting the first Fast-Finalization Certificate (FFC).

To incentivize timely participation, Alpenglow rewards validators for voting and relaying data, with additional bonuses for being the first to submit certificates. This mechanism, while well-intentioned, opens the door to timing-based exploitation.

Consider a validator v controlling X% of the total stake, where X is large enough to push cumulative notarization votes past the 80% threshold. During the first round of voting for a block b in slot s, validator v monitors the notarization votes received in its Pool. The strategy works as follows:

This strategy has asymmetric risk: the validator either receives the normal reward (if it fails) or both the normal and special reward (if it succeeds), with no penalty for delayed voting. As such, validators with low-latency infrastructure and accurate network estimation have an economic incentive to engage in this behaviour, reinforcing centralization tendencies and undermining the fairness of the reward distribution.

In this section, we examine how inherent randomness in task assignment affects validator rewards. Even if a validator fulfils every duty it’s assigned (voting, relaying, repairing), the Alpenglow protocol still injects non-determinism into its reward streams. Voting remains predictable, since every validator casts a vote each slot, but relay income depends on the stochastic selection of one of Γ relays per slot, and repair income depends both on being chosen to repair and on the random need for repairs. We use a Monte Carlo framework to isolate and quantify how much variance in annual yield arises purely from these random sampling effects.

In our first simulation suite, we fix a validator’s stake share and vary only the split between voting and relay rewards, omitting repair rewards for now to isolate their effects later. Concretely, we let

for each (f_relay, f_vote) pair, and for each epoch in the simulated year, we:

First simulations assume a stake share of 0.2% and a network-wide stake rate of 65%. This framework lets us see how different reward splits affect the dispersion of APY when relay selection is the sole source of randomness.

The plot above shows the Probability Density Function (PDF) of APY obtained by varying the Relay rewards share. We can see that up to a 50% split, the variance is not dominating the rewards, where the APY is approximately 6.75% from the 5th percentile (p05) to the 95th percentile (p95).

If we reduce the stake share to 0.02% (with current stake distribution, this corresponds to the 480th position in validator rank - 93.5% cumulative stake) we see that 50% share has some variability that may affects rewards. In this scenario, APY varies from 6.74% for p05 to 6.75% for p95. Even though a 0.01 percentage-point spread seems negligible, over time and combined with other asymmetries, it can create meaningful divergence in rewards.

Accordingly, we adopt a 20% relay‐reward share for all subsequent simulations. Indeed, we can see that, by fixing the relay‐reward share at 20%, the spread in APY distribution is mostly negligible moving from 0.02% stake share to 2%.

With repair rewards added, we now set

We also assume that 5% of slots on average require a repair fetch.

Running the same Monte Carlo simulations under these parameters reveals two key effects:

Solana has one of the highest staking rates among all blockchains. As of now, 65% of the circulating SOL is staked, which is significantly higher compared to ETH’s 29%. Several factors contribute to this difference, including the attractive yields ranging from 8% to 12% that Solana provides, as well as a positive outlook for SOL’s performance among its holders. However, another important factor is the Solana Foundation Delegation Program (SFDP), which accounts for a significant portion of the staked SOL.

Helius wrote a comprehensive and detailed piece about the Program, but almost a year has passed since its publication, making it a good time to revisit the subject. In this article, we will examine the current state of the program to understand its effect on Solana’s validator landscape and what the network might look like if the SFDP were to end.

The Solana staking market can be categorized into three distinct segments:

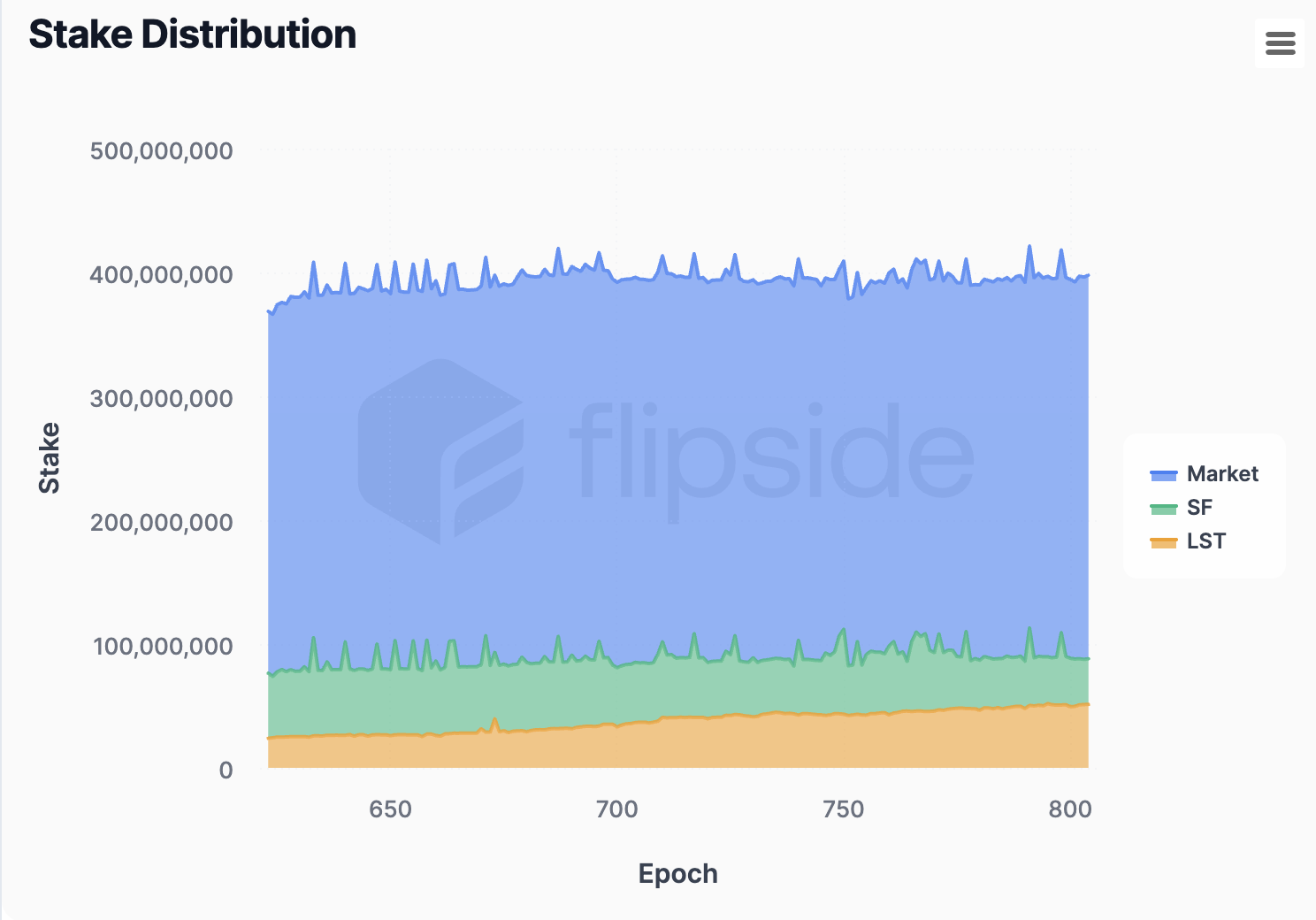

As of epoch 804, the total amount of staked SOL is 397 million, with the general market delegating 309 million, the Solana Foundation 37 million, and LSTs contributing 51 million. Over time, we have seen steady growth in LST stake and a decrease in SF delegations, which now make up slightly less than 10% of the total stake.

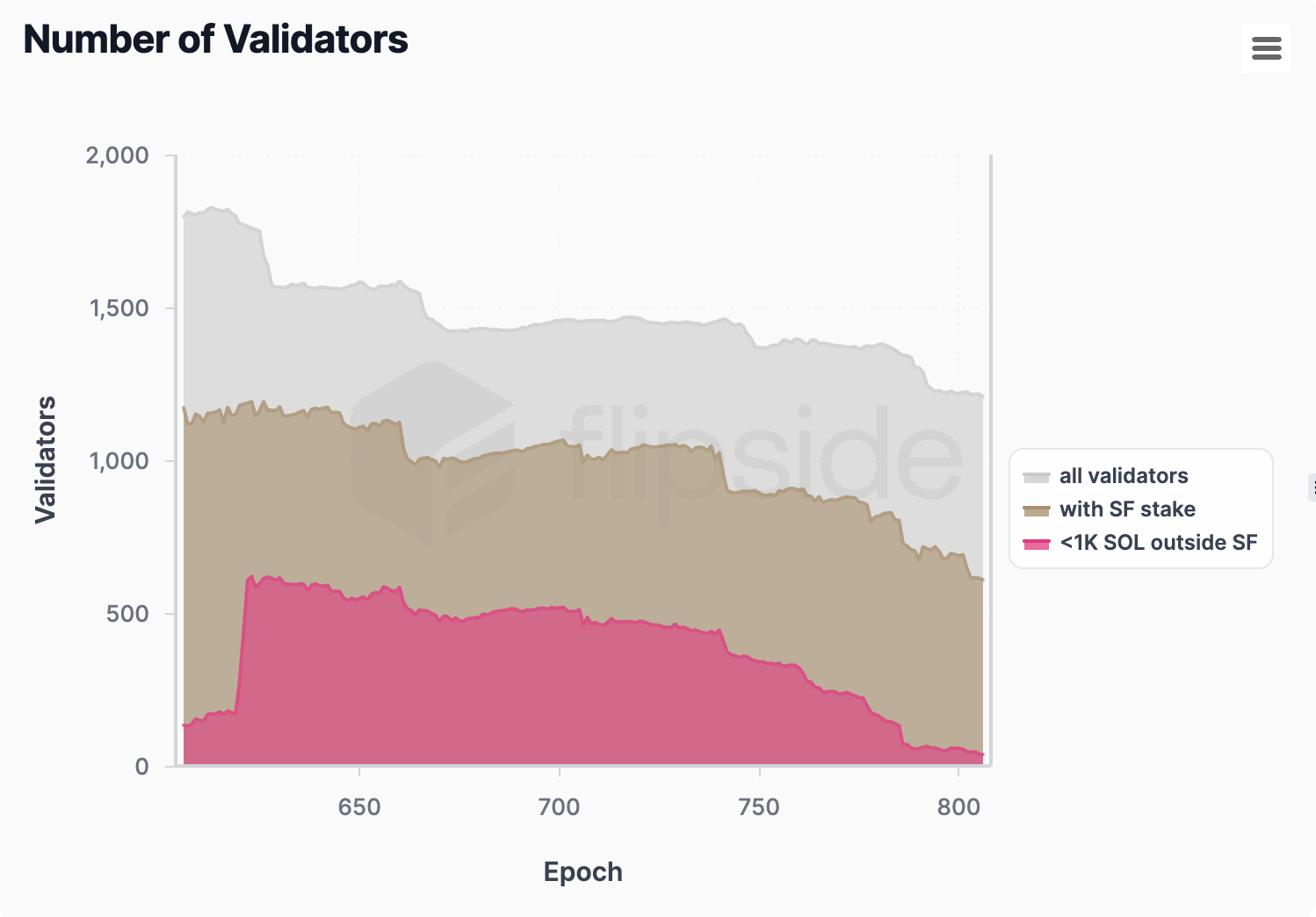

Solana stake is managed by a total of 1,216 ****validators, down from a peak of 1,800. The number of validators receiving delegations from SFDP has decreased from over 1,100 to 616, which still makes up 50% of the entire validator set, representing a significant decrease from the initial 72%. We also observe the validators with less than 1K SOL delegated outside of SF—currently at 46, down from over 600.

The 1K SOL threshold is important because SF decided to stop supporting validators that receive a Foundation delegation for more than 18 months and are not able to attract more than 1K SOL in external stake.

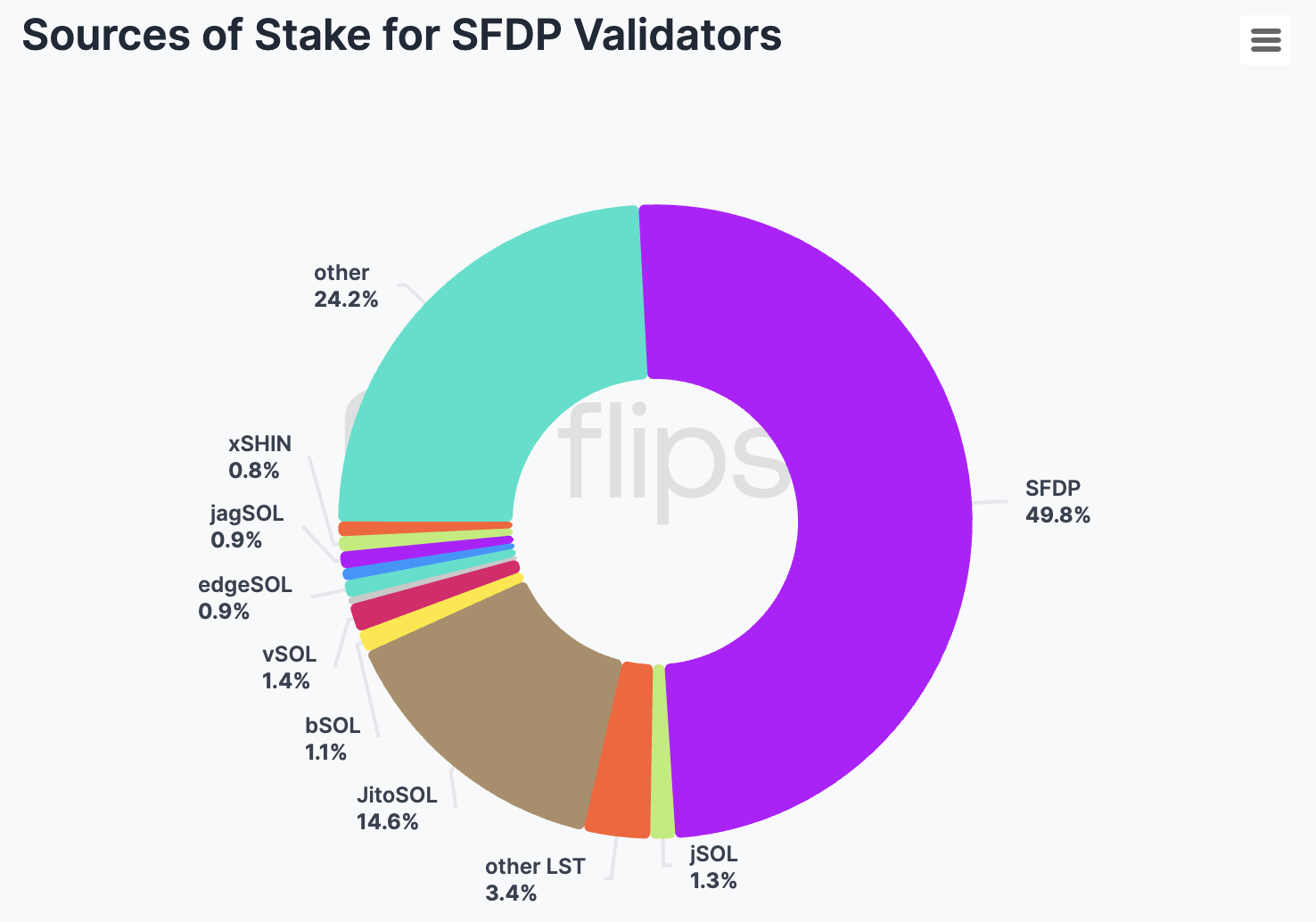

Delegations from the Program make up 49.8% of the total stake delegated to validators participating in SFDP. This is significant, but it also shows that over half of the stake comes from other sources, which is a positive sign.

Another opportunity (or lifeline) for smaller validators is provided by LST staking pools, which collectively make up 26% of the stake delegated to validators participating in the SFDP. Notably, the Jito stake pool, represented by the JitoSOL token, has accumulated 17.8 million SOL out of a total of 397 million SOL currently staked. Due to this substantial amount, being one of the 200 validators receiving delegation from the pool is highly rewarding, currently by around 89K SOL. Of the 17 million native SOL in the Jito pool, nearly 11 million, or 65%, ****are delegated to SFDP participants.

For Blaze (bSOL), another popular staking pool, 0.8 million of the 1.1 million SOL, accounting for 72%, is delegated to SFDP participants. For JPOOL (jSOL), it’s 83%, and for edgeSOL, it’s as high as 87%. Many of the LST pools highly depend on outstanding voting performance, resulting in a cut-throat competition between validators to receive delegation. The validators often run backfilling mods to increase the vote effectiveness and receive stake. Chorus One has analyzed these client modifications in a separate article.

We also observe that the SFDP and LSTs are vital for maintaining Solana's decentralization. This results from the geographical restrictions imposed by the Foundation and staking pools on validators.

When examining the total stake of validators participating in SFDP, only 31 had accumulated more than 300K SOL, while 249 had less than 50K SOL delegated.

Looking at the top 20 validators individually, the validator with the highest stake, Sanctum, accumulated a total of 850K SOL in delegations. In contrast, the 20th validator's total stake drops to 351K SOL. The size of the SFDP delegation doesn’t exceed 120K SOL in this group.

In the remaining group of 589 validators, the median total stake is 65K SOL, and the median SF delegation is 40K SOL, indicating that many validators rely heavily on the Foundation for their operations.

The node operating business has become very competitive in recent years. This is especially true on Solana, where validators often run modified clients or lower their commissions to unhealthy levels to gain an advantage. And like any other business, you can't stay unprofitable for too long.

And what does too long mean on Solana? To answer this question, we group validators into cohorts. We group time into periods of 10 epochs: every 10 epochs, a new period starts. Every period, a new cohort of validators emerges. We can follow these cohorts and see how the composition of the validator set changes over time, and in which period the validators started. For this analysis, we only consider validators with at least 20k SOL at stake.

Based on the first graph, the survival rate for most cohorts falls below 50% after approximately 200 to 250 epochs. Similarly, the second graph shows that validators who started around epoch 550 see the steepest drop in survival rates. This suggests that the too long in terms of unprofitability on Solana means around 250 epochs.

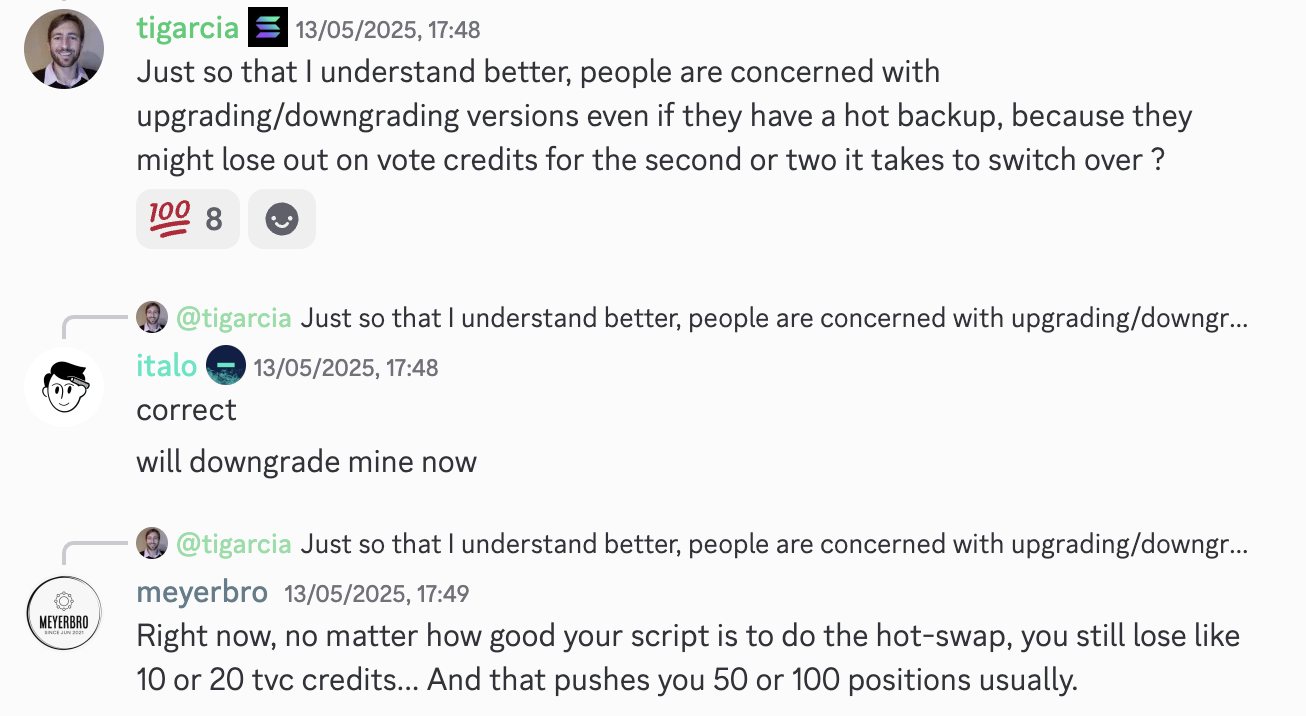

One indicator of how fiercely competitive the smaller validator market has become is the scramble to join the JitoSOL set, where validators hesitate to upgrade the Agave client because they risk losing several vote credits during the update. Any loss of vote credits is problematic since Jito updates the validator pool only once every fifteen epochs. Additionally, being outside the set decreases a validator’s matching stake from SFDP. Therefore, with the current 89K SOL Jito delegation goal, a validator could lose 178K stake if something goes wrong during the update.

Validators earn revenue via:

Of the three on-chain traceable revenue sources, MEV and block rewards are highly dependent on network activity. In contrast, inflation rewards are a function of the Solana inflation schedule and the ratio of staked SOL.

Validator performance also impacts yields. Opportunities to increase inflation rewards are limited, as almost all validators receive close to the maximum vote credits possible. Some validators overperform in voting, but APY gains from it are close to a rounding error—0.01%. Currently, the inflation rewards produce the highest gross (before commission) returns of around 7.3% annually, when compounded. The most effective voting optimizations include mods that enable vote backfiling. This opportunity, however, could be short-lived as intermediate vote credits update rolls out in the coming months. That is, unless the update is entirely abandoned because of the introduction of Alpenglow.

MEV tips and block rewards see higher upside from optimizations. Based on current activity (June 2025), tips yield between 0.75% and 0.9% in annualized gross APY, while block rewards yield between 0.55% and 0.65%. Both have a luck factor in it—if there’s a particularly juicy opportunity, e.g., for arbitrage, the searchers will be willing to pay more to extract it. Thus, the bigger the stake the validator has, the higher the chance it will receive outsized tips or block rewards. The validator optimizations for MEV tips and block rewards involve updates to the transactions ingress process or the scheduler.

In absolute terms, all revenue sources depend on the stake a validator has.

Solana is infamous for its high-spec hardware requirements and the overall costs it imposes on validators running the nodes. These costs include:

The total cost of running the Solana node, excluding any people costs, in June 2025 ranges from $90,000 to $105,000.

To establish the profitability of a validator participating in an SFDP, we will:

On the revenue side:

On the costs side:

With the above assumptions, we measure the profitability of validators participating in SFDP considering their: (1) total active stake; (2) only outside stake, without SF delegation; (3) only outside stake, but assuming no voting costs.

If the current market conditions and network activity remain unchanged for the entire year, in the first group**,** 295 SFDP validators would be profitable (48%), with a median profit of $134,283. Conversely, 319 validators are facing a median loss of -$51,473.

It is important to note that the graphs in this section are capped at $700,000 on the y-axis for clarity; however, some validators have profits that exceed this amount.

However, the stake received from the Foundation is not evenly distributed among all validators. The average stake delegated from the Program to profitable validators is 94,366 SOL, while to unprofitable ones, it is only 26,969 SOL.

The last profitable validator holds a stake of 33,242 SOL from SFDP and 21,141 SOL from outside sources, which enables it to earn $1,710.

There is a noticeable difference in commissions between the profitable and unprofitable groups: the profitable validators have an average inflation commission of 1.92%, compared to 1.51% in the unprofitable group. Similarly, the average MEV commission in the profitable group is 7.36%, compared to 5.44% in the unprofitable group.

Things get less rosy if we consider only the outside stake, without the SFDP delegation. The number of profitable validators decreases to 200, which accounts for 32% of the total, with a median profit of $35,692. The number of unprofitable validators increases to 414, with a median loss of $78,912.

The last profitable validator has 95,030 SOL in outside stake (although, with 0% inflation and MEV commissions) and earns $126.31. The minimum outside stake guaranteeing profitability is 56,618 SOL, with commissions at 5% inflation and 10% MEV. This is enough to get $5,441.52.

Among the profitable validators, the average inflation commission is 1.75%, while the average MEV commission is 7.57%. For the unprofitable nodes, the commissions decrease to 1.7% and 5.8%, respectively.

It is well known that voting costs impact validators the most. With the SOL price at $161 (as used in this analysis), validators spend around $59,063 on voting only. For this reason, node operators have long advocated for the reduction or complete removal of voting fees. This wish will be finally fulfilled with Alpenglow, Solana’s new consensus mechanism announced by Anza at Solana Accelerate in May 2025. It is ambitiously estimated that the new consensus will replace TowerBFT in early next year.

We analyze the scenario in which voting doesn’t generate costs. Even if we only consider the outside stake, it makes a big difference.

The number of profitable validators increases by 50%, from 200 to 303, compared to the second scenario. The median profit in this group reaches $74,328. While there are still 311 unprofitable validators, the median loss falls to $23,576.

The minimum stake required to guarantee profitability is 17,988 SOL, representing a 68% decrease compared to the scenario that includes voting costs.

Still, the difference in average commissions is impactful—1.92% on inflation and 7.29% on MEV in the profitable group compared to 1.51% and 5.47% in the unprofitable one.

The SFDP continues to play a vital role in the Solana ecosystem. Recently, the Foundation has shifted its focus to support validators who make meaningful contributions to the Solana community and actively pursue stake from external sources, aiming to create a more engaged and sustainable validator network.

With a more selective approach from the Foundation, LSTs come as a crucial source of stake for smaller validators. SOL holders like them, which is evident in their constantly increasing stake; however, the competition to get into the set is prohibitively tough. Still, the importance of SFDP’s stake matching mechanism cannot be understated in light of delegations from LSTs.

Together with LSTs, the SFDP stake makes up 22% (88 million SOL) of the total SOL staked. Since both impose geographical restrictions on validators, they are crucial to keep Solana decentralized in an era where even negligible latency improvements from co-location are exploited.

Currently, many validators remain unprofitable, even with support from SFDP. Commission sizes play a role here—setting them too low doesn’t seem to help with getting enough stake to run the validator profitably.

Another force negatively impacting the validators’ bottom line is voting cost. When network activity and SOL price are high, this is the time when validators should offset the periods with little action. Unfortunately, due to the voting process, a significant portion of revenue is lost. The solution, Alpenglow, is on the horizon, and it cannot come fast enough to reduce pressure on validators. Eliminating the voting costs should enable the Solana Foundation to step away further and let the network develop on the market’s terms, without excessive subsidy.

Written by @ericonomic & @FSobrini

The Berachain ecosystem is about to transform significantly with the upcoming Bectra upgrade, which introduces multiple critical EIPs adapted to Berachain’s unique architecture. Perhaps, the most revolutionary EIP is EIP-7702, which enables regular addresses to adopt programmable functionality.

This major milestone also introduces a game-changing feature BERA stakers have been waiting for: the ability to unstake their tokens from validators. Until now, once BERA was staked with a validator, it remained indefinitely locked. Bectra changes this fundamental dynamic, bringing new flexibility to the Berachain staking landscape.

Bectra is the Berachain version of Pectra, the latest Ethereum hard fork that introduced significant improvements to validator flexibility and execution layer functionality. For those interested in a deeper technical analysis of the upgrade, we recommend reading Chorus One’s comprehensive breakdown on Pectra: The Pectra Upgrade: The Next Evolution of Ethereum Staking.

Although the biggest Bectra change might be EIP-7702 (account abstraction), the biggest change for Berachain that is different from Pectra is the ability for BERA stakers to withdraw their staked assets from validators. This fundamentally alters the validator-staker relationship, as validators must now continuously earn their delegations through performance and service quality.

How Unstaking Works

As a user who has staked BERA with a validator, it's important to understand that you don't directly control the unstaking process. Here's what you need to know:

Important Considerations:

Redelegation Process

There is currently no direct "redelegation" mechanism in the protocol. If you want to move your stake from one validator to another:

During this process, you won't earn staking rewards while your tokens are in the unstaking phase.

Staking Process

The staking process itself remains unchanged with the Bectra upgrade. Users can still stake their BERA with any validator, and the validator continues to receive all rewards at their Withdrawal Credential Address.

If there are multiple stakers delegating to a single validator, the protocol does not automatically distribute rewards to individual stakers; this must be handled through off-chain agreements with the validator or through third-party liquid staking solutions.

The introduction of validator stake withdrawals transforms the staking landscape on Berachain in several important ways:

New Staking Dynamics

For BERA stakers, the ability to unstake creates:

Competitive Validator Landscape

This new mobility creates a more competitive environment where:

This competitive pressure should drive validators to optimize operations, potentially leading to better returns for stakers and improved network performance.

New Responsibilities With greater flexibility comes increased responsibility:

This creates an opportunity for stakers to be more strategic with their decisions and potentially increase returns by selecting the best-performing validators.

As the Bectra upgrade introduces more competition among validators, choosing the right validator becomes increasingly important. Chorus One stands out as a premier choice for several compelling reasons:

Industry-Leading ARR

Chorus One consistently delivers some of the highest ARRs in the Berachain ecosystem thanks to Beraboost, our built-in algorithm that directs BGT emissions to the highest-yielding Reward Vaults, maximizing returns for our stakers.

Currently, our achieved ARR for BERA stakers has ranged between 4.30% and 6.70%, with longer staking durations yielding higher returns due to compounding effects. For comparison, most BERA LSTs offer an ARR between 4.5% and 4.7%. Our ARR pick up is achieved via our proprietary algorithm (ie, BeraBoost) as well as with active DeFi, also capturing part of the inflation going to ecosystem participants:

Additionally, in terms of incentives captured per BGT emitted (a key metric reflecting a validator’s revenue efficiency), our validator consistently outperforms the average by $0.5 to $1:

Unmatched Reliability and Experience

As a world-leading staking provider and node operator since 2018, Chorus One brings extensive experience to Berachain validation. Our infrastructure features:

Transparent Operations & Dedicated Support

We believe in complete transparency with our stakers, with publicly available performance metrics and regular operational updates. Our team is always available to assist with any questions about staking with Chorus One.

The Bectra upgrade represents a significant evolution for Berachain, giving stakers the freedom to unstake and move their BERA between validators. This new flexibility creates both opportunities and responsibilities, as stakers can now be more strategic with their delegations.

In this more competitive landscape, Chorus One stands ready to earn your delegation through superior performance, reliability, and service. Our commitment to maximizing returns for our stakers, combined with our extensive experience, makes us an ideal partner for your BERA staking journey.

Stake with Chorus One today and experience the difference that professional validation can make for your BERA holdings.